Why Do Jews Pray For The Dead?

Dear Jew in the City,

The Calling has the Orthodox detective saying a prayer (Kaddish) over every dead body he finds. Why do Jews pray for the dead?

Sincerely,

Jon

Dear Jon,

Thanks for your question. I haven’t seen The Calling so I can’t comment directly on the show, but there seems to be sufficient information in your question for me to address it. I accept your statement that an Orthodox detective recites Kaddish over every murder victim. If this is the case, then it’s a nice gesture but ultimately pointless. I’ll explain why in a bit but first let me address your actual question.

“Why do Jews pray for the dead?” You are correct that Jews pray for the dead but incorrect that the prayer is Kaddish. Well… you’re incorrect in a way that the prayer is Kaddish. It kind of is, but not the way people usually think. I’ll explain that part now.

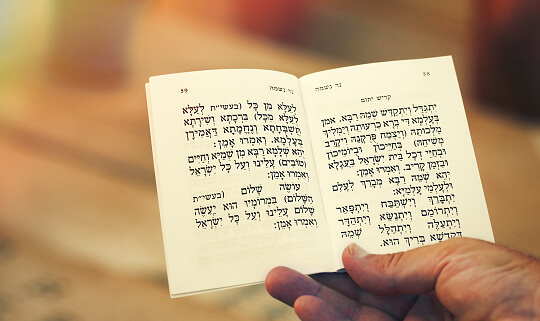

Kaddish is a prayer that praises God. It says nothing about death and we don’t mention the deceased. There are quite a number of occasions on which we recite Kaddish, including at the end of a section of prayer, following the study of aggadata (the non-legal portions of the Talmud), and at a siyum (the conclusion of a volume of Torah learning). All told, there are five different types of Kaddish, one of which is Kaddish yasom – literally “orphan’s Kaddish,” but commonly translated as “Mourner’s Kaddish.” The ubiquity of this Kaddish is why people often assume that Kaddish is “a prayer for the dead.”

The reason a mourner recites Kaddish is explained in a story that appears in at least half a dozen sources, with some of the details varying from telling to telling. The following version is based primarily on the “Minor Tractate” of Kallah Rabbasi (2:9), in response to the question of whether a person can atone for his parent’s sins.

Rabbi Akiva once saw a man struggling under a heavy burden. Rabbi Akiva was concerned that this might be an overworked slave but it turned out to be the soul of an unrepentant sinner whose punishment was to gather wood, which was then used to burn him daily. He told Rabbi Akiva that the only way to free him was if his son would stand in front of the congregation and say “Barchu es Hashem hamevorah” or “Yisgadal v’yiskadash…,” causing the congregation to respond, “Baruch Hashem hamevorah l’olam voed” or “Yehei shmei rabbah…,” respectively. (These are the prayers of Barchu and Kaddish, in which the leader of the service calls upon the congregation to praise God, which they then do.)

Rabbi Akiva tracked down the man’s wife and circumcised the deceased’s son. When the child was old enough, he tutored him and taught him how to daven. As soon as the boy recited the appropriate prayers in shul, his father’s soul appeared to Rabbi Akiva in a dream and informed him that he had been relieved of his afterlife torments.

This tale does not represent the origin of Kaddish, merely the practice for mourners to recite it. So it’s not “a prayer for the deceased” in the sense that most people think, but we do recite it “for” the dead in the sense that it’s a merit for the deceased to be an impetus for the congregation to praise God.

This is why the detective reciting Kaddish over the body of a murder victim is a nice gesture but nothing more. Kaddish is what’s called a davar sheb’kedusha – a prayer that is only recited in the presence of a minyan (a quorum of ten adult Jewish men). The entire point of the prayer is to cause the congregation to praise God; if there’s no congregation, reciting it by oneself doesn’t accomplish its purpose. (Also, even with a minyan, we don’t just randomly recite Kaddish whenever we feel like it. It needs to be recited in its proper place in the prayer service or in some other appropriate context.)

The actual prayer for the deceased in the sense that we’re praying for the deceased is Yizkor, which is recited on the last day of various Jewish festivals. While many people who don’t attend shul year-round show up on days on which Yizkor is recited, Yizkor doesn’t require a minyan and can be recited just as effectively at home. The main point of Yizkor is that one commits to donate charity in merit of the deceased. This is why Yizkor is traditionally preceded by an appeal in shul but, even when reciting it at home, one should commit to give tzedaka to an appropriate recipient and then follow through on that commitment. (You can learn more about Yizkor here.)

So Yizkor is a “prayer for the dead.” Kaddish is a prayer praising God that is recited as a merit for the deceased, as well as for a number of other reasons. But reciting Kaddish without a minyan isn’t reciting Kaddish at all because the prayer inherently requires a minyan. Unless the detective calls over nine other Jewish cops, and properly contextualizes the prayer, he hasn’t really done anything of significance. (As always, don’t get your information about Judaism from TV shows!)

Sincerely,

Rabbi Jack Abramowitz, JITC Educational Correspondent

Follow Ask Rabbi Jack on YouTube

If you found this content meaningful and want to help further our mission through our Keter, Makom, and Tikun branches, please consider becoming a Change Maker today.

3 comments

Sort by

Is praying to Hashem in the name of the dead idolatry?

No – it’s praying to God in the merit of someone – not to them.

Dear Rabbi Jack Abramowitz,

Question:

Why did the Jews pray for the dead in the Old Testament, but not in the Mourner’s Kaddish which is only for the living?

“But if he did this with a view to the splendid reward that awaits those who had gone to rest in godliness, it was a holy and pious thought. 46Thus he made atonement for the dead that they might be absolved from their sin.” 2 Maccabees 12:45-46

Why and when did this change?

And as you no doubt know, Roman Catholics don’t just pray for the the dead, but to the dead (Mary and many Canonized Saints).

I look forward to your response!

Thank you!

Shalom,

James Sundquist