My Orthodox Grandfather’s Fight Against Cannibalism in WWII

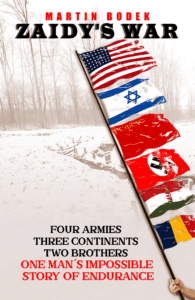

Zaidy’s War is the life-story of my grandfather, centered tightly around the events of WWII and his constant struggle between his Jewish identity and survival.

My grandfather’s story involves serving four armies under wildly unique circumstances, being present for both the largest land invasion in human history and the final battle of WWII, avoiding cannibalism under pain of death, surviving to walk 1,600 miles to his home country of Romania, emigrating to Israel, surviving the pummeling of his new community of Haifa during the Six Day War, finally settling in peace in the U.S. where he served as a chef for 40 years, and finished Shas (the entire 37 tractates of the Talmud) 14 times while he was doing all that. He passed away 8 years ago at the age of 95.

He ranged so far, traveled so wide, and was involved in so much that my wife referred to him as “The Forrest Gump of WWII.”

He was even faced with the horrifying challenge of cannibalism — the way he had to grapple with that as he attempted to uphold his Jewish faith made an enormous impression on me, as you’ll see below.

In the excerpt that follows*, Zaidy stands at the precipice of the gates of death, because he will not partake in the cannibalism that is forced on the people around him. It is in this stand though, that he actually returns to life.

–

NORTH

In early 1942, my grandfather is, once more, loaded onto a truck that is part of a large convoy. There is slightly more room than last time, with measurably more food, and he notices that he is surrounded by strong individuals, much like himself. He is being naturally selected every time he is on another involuntary trip. The nature of war has weeded out those ill-equipped to withstand this constant barrage of miserable suffering. My grandfather and the men in his company are surviving because they are the fittest. Nature is cruel, but it is why these prevailing men are still here.

The convoy rumbles on for several days, bearing north for the entire journey. After several days, they finally arrive at their destination.

In the Volga-Vyatka region, in the northeast portion of the East European Plain, to the west of the Ural Mountains, 956 kilometers northeast of Moscow is a major, bustling, well connected, heavily resourced city called Kirov. The outskirts of Kirov are an administrative division called Kirov Oblast, known as Kirovsky Oblast.

The Arctic Circle is only 886 kilometers north of this area. The days last up to 20 hours. The winters are long, severe, cold, and can last up to ten months. The summers are short, warm, and frequently interrupted by invading cold blasts from the north.

The climate is harsh, and January is the harshest month of all. The average temperature is 5 degrees Fahrenheit (-15 degrees Celsius); the record low is minus 64 degrees Fahrenheit (-53 degrees Celsius). It snows 150 days of the year, and the sun does not show its face all winter.

Upon arrival, my grandfather learns that he will carry out the same wood-chopping duties that he performed at the previous camp in the south, but he will not just serve to keep the camp personnel warm at base, and the soldiers in the battlefield, but almost the rest of Russia in the larger region as well. The wood not used in the camp will be sold, and the proceeds will continue to fund this mighty war.

It is for this additional reason that the work is incentivized. Those who produce less than the daily quota receive basic rations; those who meet or exceed the daily quota eat well, most particularly with breads and grains.

My grandfather eats well.

As the war carries on, and as the Germans continue to work to cut off Russian supply lines, resources begin to deplete, and available quality food begins to dwindle. At a critical point in the Soviet Union’s efforts to fend off the encircling Germans, the food supply for the camp runs down to zero. There is nothing for anyone to eat. An army marches on its stomach, it is said, and this army has nothing to march on.

What there is in plentiful supply, however, is human bodies. They are impossible to bury in the permafrost, but they are well preserved in this frozen hellscape.

The command comes down from the camp administration that, in the interest of survival, and until new provisions can be secured, it will be necessary to consume the deceased. The kitchen staff is ordered to make the preparations appropriately, and to sustain the camp from this supply, until further notice.

My grandfather is now faced with a choice: partake of this forbidden fare, and live, or refuse it and die. He makes an interesting decision.

THE DECISION

My grandfather decides that he will have no part of cannibalism. He will not damage his body, nor his soul, by allowing himself anything this forbidden.

He did not come all this way – dragged into four armies, foraged through villages and forests, carefully learned to discern nature’s healthy foods from dangerous foods – to find himself looked after by a kosher chef in the middle of nowhere, only to freely abandon his uncompromisable principles. Absolutely not. Under no circumstances.

This does not sit well with Yerucham, who considers my grandfather to be one of his wards. The others in the camp are eating reluctantly, but decently. They are getting enough calories to get through the day, but my grandfather is refusing. He fasts willingly for a full day. Yerucham keeps cajoling, offering different cuts, as it were, to see if he can convince my grandfather to have just a bit. His friend’s survival is at stake, but my grandfather is not hearing it. He fasts for a second day, and he begins to waste away. None of Yerucham’s efforts to convince my grandfather that this partaking is permissible under the circumstances takes any effect whatsoever. My grandfather will not have it. “B’shim oifen nisht!” is the powerful Yiddish phrase my grandfather used to express his refusal.

On the third day, a Soviet officer learns of my grandfather’s hunger strike and gives him a few quick blows for his insolence. He is now starving and bruised.

Yerucham tries a final tactic. There is some bread available, but the soldiers receive them on priority. Some scraps do trickle down to the laborers, but they are not enough to sustain anyone’s life. Yerucham knows how the food is apportioned, but he also knows that my grandfather needs proteins if he is to survive any further. Yerucham withholds the bread from my grandfather in an attempt to make him choose the protein-rich food. He tells my grandfather that he does not know how much longer he can hold his position as chef. If he loses the job, then what is my grandfather going to do?

My grandfather is unmoved.

After nearly three days of fruitless coaxing, Yerucham sees that his efforts are fruitless, and that his friend is starving to death. He resorts to different means to assist my grandfather. He scours the entire kitchen and grounds for scraps of anything, and he heads out into the cold to forage. He pieces together meager rations and gives them to my grandfather. He then manages to secure some of the bread loaves for him. My grandfather comes back from the brink.

Miraculously, the camp is resupplied the very next day. My grandfather stands by his conviction, never staining his body or his soul, and he is rewarded for his efforts. The camp reverts to the usual diet, and sets aside the verboten, but wholly necessary, stopgap nutrition measure.

Out in the frozen tundra, however, this temporary reliance has had a psychological, permissible effect. It is now not a last resort when experiencing deep hunger.

One snowy evening, out in the field, when the working group could not make it back to the camp in time for the night, a gruesome scene unfolds. The laborers sleep in trenches huddled upnext to each other, and in tight circular formations, like penguins in the Arctic. One man’s head rests on another man’s shoulders. My grandfather’s head is resting on a corpulent fellow’s shoulders, who offers good warmth. Another man – bewildered, starving, and desperate – produces a knife, walks over to the large man, pulls down the back of his pants, and begins cutting into the flesh of his buttocks. The victim does not shout out, neither does he yelp, nor does he scream. He simply reacts by remaining perfectly still, and whispering, “Brother, don’t cut. I’m still alive.” The cutter withdraws the knife, slumps his shoulders, and returns to his sleeping position in the group.

So it goes for my grandfather, for Yerucham, and for the soldiers and laborers in the camp. The population numbers dwindle and the war rages on, through the cold, the bone cold, and the bitter cold.

Days stretch into weeks, which stretch into months, which stretch into years.

The weak and the unfortunate die. The strong and the lucky survive. My grandfather carries on. His priority every day is surviving to the next day. Perhaps one day he will know freedom. Perhaps one day he will be home.

–

*Please note the excerpt may have been edited for length and clarity.

Zaidy’s War came out in October of this year. To read more, you can purchase the book here.

If you found this content meaningful and want to help further our mission through our Keter, Makom, and Tikun branches, please consider becoming a Change Maker today.

6 comments

Sort by

May we never be tested with such nisyonos. Mr. Bodek, what a zechus to count yourself among his descendents and share his story… Yehi zichro Boruch…

Amen. Thank you, and bless you.

I have great admiration for this man who held onto to his principals! This story is a real inspiration! It is inspiring to see an example of someone who had beliefs that helped him be his best self even though every single person around him tried to convince him to do otherwise!

This is a beautiful example of religion bringing out the best in a person!

Thank you kindly. My grandfather has inspired me always, and it’s gratifying that through this work, he can inspire people beyond the bounds of his own family and community.

What a fantastic and inspiring story!

Thank you kindly!