Rebuilding With Light: This Orthodox Jewish Woman Led A Team That Rebuilt The World Trade Center

The 21st anniversary of the falling of the Twin Towers is on Sunday. Like many, I have distinct memories of September 11, 2001: I was in second grade, and was already in my Brooklyn classroom davening shacharis by the time the first plane crashed into the North Tower. While understanding the gravity of the situation, my classmates and I were still disappointed that our teachers didn’t let us have recess on the playground out of fear of additional attacks. The next morning, I walked to school with a heavy heart, the crisp autumn morning smelling like smoke instead of fresh air, and burned pieces of newspaper fluttering over the ground instead of fire-colored leaves.

About a year later, my local library received a piece of the beam from one of the towers, and I would often pass the display and think about that morning after, and my seven-year-old self’s shocking understanding of how dark the world could be.

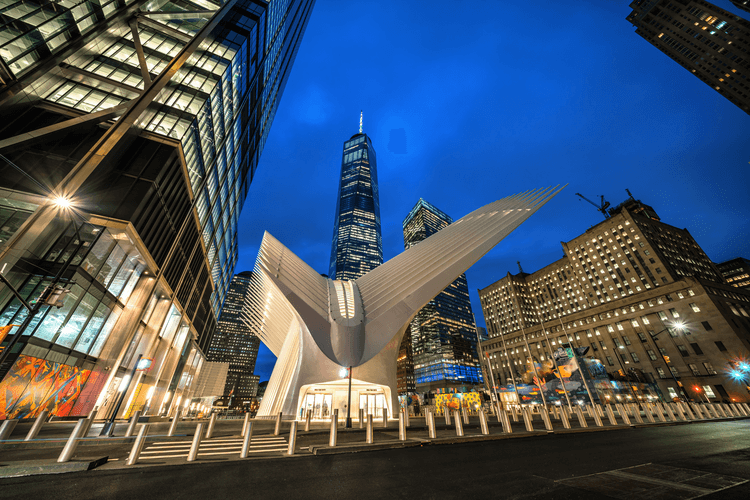

Now, Ground Zero is a place of commemoration, but also light in the wake of tragedy.

The sixteen-acre complex is divided into halves. In one part, the Freedom Tower stands tall. Then, eight acres are devoted to the footprints of the original Tower, as embodied in the reflecting pools. This aspect of the memorial has an auditory component as well as a visual one which signifies endless flow. The multisensory component was well-thought out. Aside from vision and hearing, you can even feel splashes of water when you’re close enough, and sense the vibration of the water as it falls and swirls. This footprint also houses the museum memorial. The other eight acres consist of what will ultimately be four office towers (there are currently three) and the Oculus. These towers signify the future of commerce and community, retail and gatherings — which memorialize the past and are a monument of perseverance to the future.

Rachel Kraus was one of the brilliant minds behind the complex — the memorial and huge retail space of the Oculus. As the Group Director of Global Brand Ventures at Westfield, she led the brand partnerships business and strategy for the retail development at World Trade Center.

Rachel grew up in Teaneck, NJ, as one of five children. Her family was Modern Orthodox with a strong traditional upbringing in tandem with a strong emphasis on contributing to society and the larger world. “One of the anchoring values for both of my parents,” Rachel says, “was the relentless commitment to Jewish identity and to practicing rituals and faith and values, coupled with bringing who you are into the world and finding your spark — and marrying both together.”

They very much taught by example: her father, a rabbi, was involved in Jewish education, psychology, and a Broadway producer — notably working with The Fantasticks. Rachel herself went to Stern College for marketing, and double-majored in music while taking some classes at Julliard; she received her MBA at NYU.

In addition to her day job, Rachel and her husband are the Directors of Community Education at Congregation Kehilath Jeshurun on the Upper East Side. They’re involved in leadership, life cycle events, giving shiurim, and more. She’s also the mother of four children.

Like many, Rachel also remembers where she was and what she was doing when she received news of the Twin Towers’ fall: She had been a student in Israel at the time. As a Jersey native, she knew many people who worked in NYC and has a slew of stories about people who had been there that day, or late.

The building of the memorial took a long time, and Rachel moved up the ranks professionally as plans began to be created. Westfield had acquired a lifetime lease of the retail at the World Trade Center about a month before 9/11. That day, the head of development was killed because he’d gone back into the building to retrieve some other team members — who ultimately made it out safely. When Rachel began working at Westfield a few years later, there was always a discussion about the company’s right-of-first-offer to come back to the World Trade Center project.

She explains, “There were a lot of complexities, many different stakeholders and a lot of questions about what was the right thing to do with the space.” Commission of public opinion, building design, and even the lengthy process of cleaning and prepping the site post-tragedy were also factors in the delay. Another complicated element is that the memorial is a partnership between the Port Authority and a number of private stakeholders. Years were spent making sure that those people as well as the public — including survivors and the family members of victims — felt that what was conceived and ultimately constructed was on-point for each party. It wasn’t until 2012 that they finalized the plans, and Rachel came on to lead the marketing and pre-development efforts on that project — a decade after the event.

Every single part of this project was intentional: Rachel describes it as a unique fingerprint in every single inch of those sixteen acres. “An extraordinary amount of thought and intention went into the design, into the flow, into the way people interact with this space — into how you create a sacred space within a public space — and thinking about everything from lighting to construction to how high the buildings are.”

When asked if it is better to visit the memorial during the day or at night, Rachel wholly recommends visiting at both times. The light component of the design was a key part of the development of the Oculus. “When the Oculus was originally concepted,” she regales, “there was a very specific intent of design about its meaning and significance.” If you were to take a bird’s eye view of the complex, all the buildings are symmetrical… save for the Oculus, which is slightly off-center.

On September 11, at 10:28 AM (the exact moment that the second tower collapsed), the sun beamed light into a specific place on a specific angle in the complex. Although the original design of the Oculus was to have it perfectly symmetrical with the rest of the memorial, they instead shifted its position so that the Oculus would reflect a perfect beam of light that mimics the angle of the sun at 10:28 AM on September 11. If you visit the Oculus on that date and time, you can see that beam of light shining in the center of the building. This is the sheer attention to detail that is put into even one element of the site — and the beautiful, awe-inspiring effect captures the power of rebuilding on this sacred site.

When asked about her personal perspective on memorializing the sites of terror attacks, Rachel recounts how she herself was at the scene of a suicide bombing in Israel at the height of the Intafada. “Every time I go back, to this day, I make the bracha Sheasa li neis b’makom ha’zeh,” Rachel confides. “I personally memorialize it in a very profound way.” The reality of life in Israel is that there are too many stories of tragedy and terrorism to make public memorials at each location.

However, she emphasizes that memorializing these events — personally or with a marker — is incredibly important. “Throughout Jewish history — going back to Biblical times — any time there was a moment or interaction there was a rock or the name of a place that then anchored what the experience was. I think that is an available option, and something that is highly impactful and valuable when it comes to grieving or memorializing, and when it comes to resilience in forward motion and thinking.”

There is wisdom in the Torah: within it, there is this notion of identifying and marking a spot where something monumental took place. This occurs whether that happens on an individual scale, or a national or global one: Yaakov marked the place where he dreamed of the angels ascending and descending the ladder with twelve stones, for example, while Yehoshua put up twelve stones in Gilgal as a monument that the Jews crossed the Jordan River into Israel on dry land. Perhaps we can even apply this lesson to the Jewish practice of placing pebbles upon graves: not only are stones more permanent than flowers, but the act of placing one assigns a tangible action to the commemoration of the deceased.

Rachel considers working on this project to be one of the most incredible privileges she’s had professionally and personally — even spiritually. The concept of rebuilding is integral to this time of year. Elul and Tishrei are built on the bedrock of teshuva, which incorporates evaluating and assessing for the purpose of personal rebuilding and improvement. The Oculus is a perfect example: “If you shift even a few degrees,” she says, “how much more light can you bring into your life? How much more meaning can you incorporate into your existence?”

The number of years the complex took to come into being — and there is still work to be done! — is also symbolic of the slow process of self-work; the amount of care and thought that went into its design is a lesson in the interconnection of the personal, communal, and global effect that bettering oneself has on the world.

If you found this content meaningful and want to help further our mission through our Keter, Makom, and Tikun branches, please consider becoming a Change Maker today.