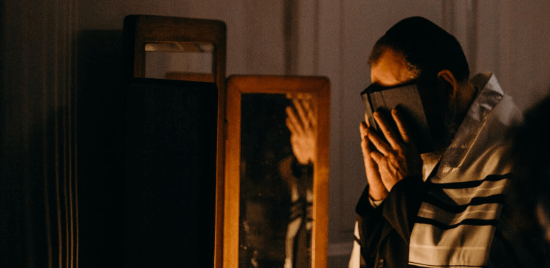

Is God Our Father, Our King, Our Beloved…Or All Of The Above?

Ani l’doni v’dodi li – I am to my Beloved and my Beloved is to me. (Song of Songs 6:3)

The Hebrew letters at the start of these four words form the word Elul, the name of the month preceding Rosh Hashana. With the “beloveds” at the center of Song of Songs being metaphors for God and His people, this acronym expresses a deep relational aspect of the High Holidays.

It is striking that we describe our relationship with God, even as He determines and seals our fates for the coming year, in terms of lovers. But it is perhaps even more striking to think about that metaphor alongside all the others. We speak of the push and pull of God as our Father and as our King in the Avinu Malkeinu prayer recited from Rosh Hashana through Yom Kippur. After each series of shofar blasts during the Mussaf service of Rosh Hashana, we recite a paragraph describing how we stand before the Judge on this birthday of the world “whether as children or as servants” – and we appeal to Him in both aspects, simultaneously seeking the mercy a child might expect from a parent and also throwing ourselves at His feet as slaves subject to our master’s whims.

Soon, we will stand before Him on Yom Kippur and repeatedly call upon Him to forgive us Ki anu amecha – “because we are Your nation and You are our God; we are your…and You are our…” – in a poem listing no fewer than 12 descriptions of the relationship between us, that prefaces each public confession litany.*

How many different relationships can one human have with one Unity?

None of these relationships is so one-dimensional in itself, either. In each case, particularly in the Yom Kippur prayer, we describe both sides of the relationship – and each side can be understood in a number of ways, with different ramifications regarding what we owe and what we might expect in this relationship.

Although we specify that we would like His fatherly mercy on Rosh Hashana, parenthood is not all about letting things slide. When studying the character of Devorah the Judge, commentaries react differently when she refers to herself as “mother in Israel” (Judges 5:7). Common stereotypes might lead us to read this maternal image as even softer and more merciful than a paternal one – and indeed, some commentators (e.g., Abarbanel) suggest Devorah is describing herself in this line as being merciful towards her nation “like a mother, who has mercy on her children.” However, in context of the book of Judges and her role as one of them, we might wonder whether it was really mercy that the people needed from their leaders. Perhaps this is why Metzudat David, asserts that she means “like a mother, who chastises her child to straighten his path; thus am I to Israel.”

When we think of God as our Father, are we hoping for blind compassion despite our faults, or would we be better served by His guidance to improve ourselves?

But whose responsibility is it really to come closer to the other? The Yom Kippur poem is prefaced by an appeal for God to forgive and atone for us, and then we say “ki” –implying, on the face of it, that we believe we deserve this forgiveness on the basis of our established relationship. We are X to You and You are Y to us; therefore, You owe us forgiveness. But is that what we are really saying? Is all the onus placed on God?

Each of the portrayals in this poem can be understood as demanding something from both sides. We may expect compassion and/or guidance from God as our Father – but we also mention our role as His children. Is that simply a passive role, in which one receives compassion and/or gets lectured at?

In Shemot 4:22, God tells Moshe that he will be called upon to proclaim to Pharaoh “Israel is My son, My firstborn” – a verse that, on its own, seems to suggest a paternal protectiveness. Hey, Pharaoh, those are My kids you’re oppressing! You’d better watch out! As if it doesn’t matter what the children do but simply who they are; by virtue of being His children, He will care for them. And that’s true. [See Kiddushin 36a, where two sages debate whether the Jewish people maintain their status as God’s children even “when you do not behave as sons.” Rabbi Meir, who argues that “either way, you are called sons,” cites several verses to support his side, in which the Jewish people are varyingly referred to as “foolish sons” or “faithless sons” or corrupt sons”; in each case they are still called “sons.” While the Gemara does not record a decisive resolution to the dispute, the Torah Temimah (on Devarim 14;1) suggests another midrashic passage, indicating the other sage ultimately agreed with Rabbi Meir.] But there’s another element as well; the next verse continues, “Send my son and he will serve Me.” The son has responsibilities to the parent as well.

Devarim 14:1 similarly refers to God’s people as His children, and at first glance, may similarly seem focused on the love and protectiveness a parent feels towards a child: “You are the children of the Lord, your God; do not cut yourselves or make any baldness between your eyes for the dead.” Any parent wants to ensure their children will not be harmed in any way and certainly would caution them against doing something to harm themselves. The father/child metaphor could be about God’s loving concern, a sentiment that might lead to His unconditional forgiveness. However, many commentators go deeper. Ibn Ezra notes the context – a cultural norm of self-harm specifically as an expression of grief at the loss of a loved one – and suggests a different perspective on God’s paternal love for His people:

Since you know that you are children to God and He loves you more than a father to a son, don’t cut yourselves over anything He might do – for everything He does is for good. And if you don’t understand it, just as young children don’t understand their father’s actions but they only rely on him – thus should you do also.

Of course, Jewish tradition acknowledges that bad things that happen; it acknowledges our pain at the loss of a loved one and even mandates mourning. But Ibn Ezra suggests the issue in this verse is with a drastic grief that reaches unhealthy extremes and leads to self-harm; he suggests the point is to keep that pain within a larger, more foundational and more positive, perspective. A parent may not always behave with the obvious loving kindness the child might want to see; being a child is not just about passively accepting love and forgiveness, but about recognizing the parent’s love even when it is not apparent, and trusting in that foundational love – not in abusive situations, but in the case of a parent setting appropriate standards for the child’s welfare and growth – to see them through even difficult patches.

If we transfer this idea to Yom Kippur, perhaps we might say that rather than coming with an entitled air of “You owe us forgiveness because we’re Your kids,” we approach God with an air of “I can trust You as my Judge, because I know that You love me and will make the best decisions for me.” Perhaps that acknowledgement is even part of what helps our growth – within ourselves and, even more so, towards our Beloved – and enables us to in fact deserve His compassionate forgiveness.

Much has been written in recent years about the confession litany recited on Yom Kippur and how some might struggle with excessive feelings of guilt; certainly, those for whom these prayers increase unhealthy thoughts should seek appropriate guidance. But confession, the deep acknowledgement that we could do better, does not have to be an exercise in self-loathing or self-flagellation (despite the symbolic strikes to the chest as we recite the litany).

When we approach God and ask Him to forgive us on the basis of our relationship, we are not coming as entitled children who think they bear no responsibility for their actions. We are responsible, and we could have done better. At the same time, we are also highlighting that God has responsibilities to us too. We are highlighting that we are in a committed relationship that goes both ways and has many facets on both sides.

The Ki anu amecha poem is rooted in a midrash that expands on a verse almost identical to the one we opened with, but in the reverse: “My Beloved is to me and I am to Him” (Song of Songs 2:16). While many an inspirational Elul speech highlights the initiative of the “I” in our verse above, suggesting that we the people must take the first step towards God in order to prompt His step towards us, this verse suggests that it goes both ways. Any healthy relationship requires commitments and movement – including initiative – from both directions.

How are we to understand all the multifaceted portrayals of our relationship with the One God? Well, He is One, but we are not.

Maybe each of us relates to God differently; maybe each of us understands these portrayals of our relationship differently, with one seeing Him as our merciful Father and another seeing Him as our guiding Father and another very differently again.

Maybe different aspects of each type of relationship are more relevant – or inspiring – to each of us at different times of our lives. We relate to Him differently at different times.

The bottom line is what we started and ended with: the verses in Song of Songs that simply state that we are beloved of each other, that we belong and move to each other. That metaphor provides the framework of a dynamic, symbiotic relationship that can weather any storm through our mutual commitments – commitments of our past, present, and future.

Our God, God of our ancestors, forgive us…for we are all of this to each other and that is stronger than any of the sins or gaps between us that we are about to confess.

Though we traditionally bow our heads while reciting the confession litany, on the inside, our heads are held high. Because we know we are God’s beloved as He is ours, and we know we will come out on the other side stronger than ever before – not only because of what He will do for us, but what we will do towards Him.

As Yom Kippur closes, we rejoice, holding our heads high on the outside as well as inside, confident in what the future holds.

*References to prayers are specific to Ashkenazi tradition and may not be part of Sefaradi liturgy.

If you found this content meaningful and want to help further our mission through our Keter, Makom, and Tikun branches, please consider becoming a Change Maker today.