Orthodox Jews Who Fought In WWII

While no one could say that observant Jewish members of the United States Armed Forces have ever had it easy, there are many trailblazers who have made it possible for today’s Orthodox Jews in the military to thrive. But what were things like for Orthodox Jews who fought in World War II? JITC Board member, Mayer Fertig, had two grandfathers who fought in World War II. According to Fertig, “Neither of [them] had patience for shtick. They were straightforward frum Jews.” Fertig sat down with us to recount their experiences and the numerous challenges they faced as observant Jews fighting in WWII

Zeidy Joe Fertig

Joseph (Yosef) Fertig helped train pilots at several bases around the country. “He stood up for his beliefs. He was married, and close to 30 years old when he enlisted. He grew up in a wealthy family and was already a pilot before the war. He was in the New York National Guard, flying anti-submarine patrols from Floyd Bennett Field in Brooklyn.”

All of this would normally have added up to a quick trip overseas but he never left the United States during the war. “We wondered why he never went, because the [U.S. military] was so desperate for pilots. I had an opportunity years ago to go up in a refurbished WWII bomber and got to speak to crew members who had flown during the war. They said that [Zeidy] must have really ticked somebody off.” This was true to the fighting spirit his family knew of. “We know that at one point in Georgia or Texas, Zeidy had a superior officer who was an anti-Semite. The man took a Chumash off Zeidy’s desk and threw it on the floor. My grandfather decked him.”

Joe Fertig used his Torah knowledge and military know-how together to help other Jewish pilots. “When he encountered a married Jewish pilot who’d had a halachic chupah, he helped him to execute a provisional get for his wife before shipping overseas, just in case he didn’t come back.”

Keeping Kosher in the Army

Joe Fertig and his wife, Esther both grew up Shomer Shabbos and were observant their entire lives. “They lived in base housing and hosted Jewish soldiers on base for Shabbos meals. They would get kosher meat shipped in from the nearest city with a kosher butcher. “My grandmother said the meat would get packed in St. Louis on dry ice and go on the bottom of a scheduled bus and she would meet the bus,” Fertig said. Sometimes there were significant complications. “One time, the butcher forgot to include the dry ice. Bubby joked that you could see the flies following the bus all the way [to the base].” The meat order that spoiled was for Pesach. According to Fertig’s aunt, Sharon Schwebel, for that Pesach, the couple ate matzah and oranges the entire Yom Tov.

“Bubby was Esther Muchnick Fertig, and one of her brothers was also in the service. Nathan Muchnick was in Army Intelligence. He spoke 10 languages including German and was sent into Germany to hunt down Nazi war criminals. He was frum and has frum great grandchildren today, as well.” During an interrogation, Nathan Muchnick discovered a painting hanging in a Nazi officer’s home that was painted on the back of a section of a Sefer Torah. That piece of klaf is still in his family, used for educational purposes.

Joe Fertig’s grandfather came to the US in 1880. He was a wealthy businessman and raised his family in New Brunswick, N.J. “My uncle Aaron Fertig once realized he forgot his wallet as he was approaching a toll on the NJ Turnpike in central Jersey. He filled out the form to pay the toll. When the toll collector saw his name, he asked if he was related to the Fertigs from New Brunswick. “Your grandfather kept food on my family’s table during the Depression,” Fertig’s uncle was told. “Go ahead.”

Grandpa Harry Leiderman

Nathaniel Harry (Naftali Hertzka) Leiderman was Fertig’s maternal grandfather. “Grandpa was a decorated combat medic in five brutal campaigns including the famous battle at Anzio. He was all over North Africa, Italy, different spots in Europe serving in the precursor to what became known later as a MASH unit, a mobile army surgical hospital. Grandpa came to suffer from what was called shell shock,” what is now known as PTSD — Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. The standard treatment for it in WWII was to come home for rest and relaxation. “He came back to the US and organized shows for the USO for the rest of the war. [This was a blessing because] most of his unit was wiped out at D-Day. He never ate treif and came home weighing 104 pounds.” Nat was already seeing his future wife, Lila Fisher, when he shipped out. “All of her letters that she wrote to him were lost, but all the ones that he wrote to her, my family still has. They had met before the war on the Lower East Side, both from frum families, and he asked her to wait for him.”

The Army Megillah Reading That Became Famous

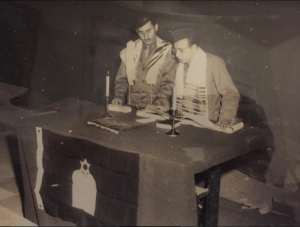

Corporal Nathaniel Leiderman reading Megillat Esther for Jewish service members in Italy, Purim 1944, with Captain Rabbi Aaron Paperman, a U.S. Army chaplain (left)

Nat’s observance in the army became well-known because, “There was a picture of my grandfather on the back of a box of Manischewitz matzah.” Manischewitz featured photos and stories of Jewish life on their boxes. “One of them turned out to be the story of our grandfather, leining megillah in Italy for hundreds of soldiers.” Nat Leiderman was kovea itim his whole life. “He was very principled. He was a frum man from birth and he lived and died and raised his family that way.”

The army did institute some practices to cater to the needs of observant Jews. “They put together certain things to make their lives easier, provided through the chaplains. But regardless, my grandfathers and thousands of other Shomer Shabbos GIs were moser nefesh during their service; they did not have it easy.” Regardless, they were proud and honored to contribute. “I’m sure that [they] felt [they] were doing important work.” The men were also patriotic Americans, and supporters of the state of Israel before it even existed. “Zeidy Joe’s family had been here since 1880. Grandpa Leiderman, for whom my younger son is named, was involved in smuggling firearms to Israel in 1948 through the Young Israel of Brooklyn in Williamsburg.” Fertig was able to speak to his Zeidy in-depth about his experience. “When I was in college, I interviewed my grandparents for a school project. Zeidy Fertig was not a very talkative guy but one thing he said that has remained with me was, ‘We wanted to get a shot at Hitler.’ Ironically, Zeidy never left the US but a lot of pilots he helped train sure did. He did his part.”

A Lasting Legacy

Zeidy Joe Fertig and Grandpa Nat Leiderman are no longer alive but both have frum great-grandchildren; Nat has a great, great-grandchild being raised in a frum home. Their legacy of fighting for freedom lives on. “My son Dovid is serving in the IDF’s Givati Brigade right now. When he started, he was very interested in becoming a medic, in large part because of Grandpa’s service.”

If you found this content meaningful and want to help further our mission through our Keter, Makom, and Tikun branches, please consider becoming a Change Maker today.