Why This Orthodox Jewish Woman Doesn’t Find Judaism Sexist

I hear a lot of comments to the effect that women are second-class citizens in traditional Judaism, and I can certainly understand where that impression comes from. Men populate the more public halachic acts, such as counting for a minyan and leading the public prayers which require one. There are various religious acts that men are told to do and women are generally told not to do – while there is almost nothing women are told to do that men are told not to do. Especially in a world that values leadership and active, visible participation to such a high degree, it might indeed seem that men have, or do, all the “Stuff,” while women are left out.

Growing up as an Orthodox girl and then woman, I’ve often wondered why I never felt this way. If it is so understandable, why doesn’t it bother me? Why don’t I feel second-class?

There are a lot of reasons, and among them is the fact that I have been blessed to learn a little Torah, including the sources behind many of those practices that rub some people the wrong way, and what I see is very different.

I see a picture of “Jewish citizenship” that rests not on rights, but on obligations. I see a corpus of halachic literature that centers on definitions, determining precisely who is mandated to do precisely what, when and how. I see a tradition of scholarship that takes those definitions very seriously, calling for each person to do what they are obligated to do, with little concern for what they want to do beyond how it does or doesn’t fit within that framework.

Modern perspectives often focus more on personal meaning than on obligations imposed from on high, and today’s generation might naturally not be too impressed by that sort of framework. I will always remember the Starbucks barista who, after I’d explained I needed to see the label on the peppermint syrup to see whether it was kosher, exclaimed “ain’t no one gonna tell me what I can and can’t eat!” But her perspective is not halacha’s. The notion of Someone telling me what I can and can’t do, in virtually every area of life, is the core and focus of halachically-rooted Jewish thought. Within that framework, as long as my obligations are taken seriously, I am indeed a first-class citizen.

In this perspective, the value of my citizenship is not determined by the number of responsibilities placed upon me, but by the question of whether it is important that I do them. Whether or not I am allowed to wear tefillin does not define my relationship with G-d or with halachic tradition; the question of whether it matters that I observe Shabbos, for instance, does. And the Torah, as well as every halachic text I’ve had the privilege to study, screams “of course it matters!”

Of course I matter.

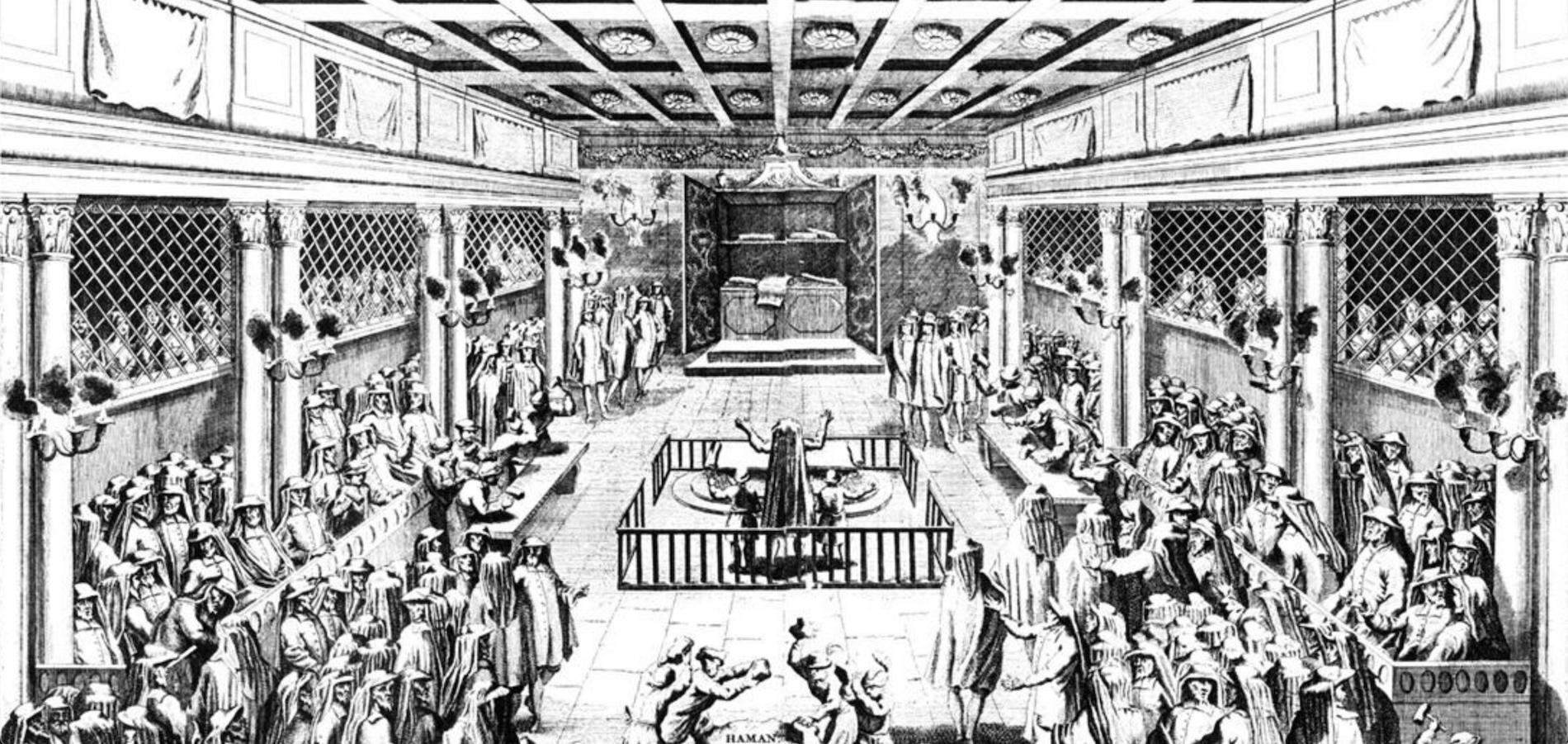

Take, for instance, the upcoming holiday of Purim and the obligation to read Megillah.

Had I never studied the laws of Purim, I might look at the public observances of the holiday with great ire, miffed that some authorities hold women cannot read Megillah for men, maybe not even for each other, maybe not even for themselves. I might be offended to be left out and told I can’t do this religious ritual myself. I might infer that those authorities who say women are allowed to read for men, or at least for each other, are more respectful of women as full Jews than those who forbid it.

But if I examine the halachic sources behind these views, I will discover that they stem from ancient texts, some of which seem to conflict with each other, and centuries of attempts to reconcile them – just like we find in every area of Jewish law, regarding halachic questions applying to all genders.

Almost 2000 years ago, the great sage Rabbi Yehoshua ben Levi cared deeply that women hear the Megillah reading (B.T. Megillah 4a), and that various scholars from his time through the Middle Ages and beyond tried to figure out the precise nature of women’s obligation. One scholar wrote that women are obligated to hear Megillah, while men are obligated to read it, and scholars ever since have worked hard to determine whether that distinction is accurate, why there would be a difference between genders with regard to this mitzvah, and what practical ramifications the distinction – if it exists – might have on our fulfillment of it.

One of my favorite bits of halachic analysis with regard to the mitzvah of Megillah is the view that women might count towards a minyan for the purpose of Megillah reading – even though women don’t count towards a minyan for daily prayers, and perhaps even if a woman cannot read Megillah on behalf of a man. (See the commentary of the Ritvaon Megillah 4a.) She counts alongside him, but she can’t read for him? How can that be? The answer is that it’s not about some amorphous notion of respect for women; respect is a given, and that’s not the point. Halacha works by analyzing each question on its own merits, based on the issues and requirements unique to that question. The purpose of the minyan for Megillah is not the same as the purpose of other minyanim, so its makeup might well be different. The mechanism by which one person may recite a prayer or text on behalf of another has particular technicalities associated with it, which may or may not have anything to do with the definition of minyan in a given case. To each halachic question, its own.

Studying the texts that hold these discussions, I find it impossible to be offended by any difference in obligation, or by the views that hold I can or can’t read Megillah for myself or anyone else – even when some of the reasons may sound odd. I am instead gratified by the extent of intellectual effort applied to figuring it out. Because these medieval scholars respected me, as a full Jew, enough to worry about my religious obligations as much as they worried about my husband’s. Because my performance of halacha matters.

As I move on through the history of halachic discussion on this question, I find that a hundred years ago, the Chafetz Chaim wrote that men must read Megillah for their female relatives at home (Mishna Berura 689:1). Here, too, I might start to be insulted at the idea I can’t read it myself, or the implication that I should hear it at home rather than going to shul. But then I might continue reading and find that he actually does say a woman may read Megillah for herself or another woman – as long as she does it properly, because in his day one couldn’t assume women were educated. (Ibid. 7-8)

The Chafetz Chaim

(And yes, we would do well today to take that point to heart and build our shuls with more careful thought to how all can best participate. I include “attend” and “hear” in my definition of what it means to “participate” – because halacha does.)

It doesn’t bother me that these discussions, definitions and analyses were carried out primarily by men for all those centuries, because I remember the realities of women’s education (or lack thereof) during that time. I am instead overwhelmed by the realization that even though few women had much of a seat at the table, all those men cared very much about determining the nature of women’s obligations. Because those obligations matter just as much as the men’s obligations are they similarly debated. I matter, in the eyes of G-d and of halacha, just as much as they do.

Of course I do.

Whether I read Megillah or hear it read, whether I hear it from a man or a woman, whether I do so in a small gathering at someone’s home or at a public shul reading – I will do it within the framework of the halachic tradition I accept as binding, a tradition that cares deeply about the things each Jew must do and the ways in which we may do them. To me, that is what matters.

If you found this content meaningful and want to help further our mission through our Keter, Makom, and Tikun branches, please consider becoming a Change Maker today.

5 comments

Sort by

Beautiful article! Thanks for approaching this topic so eloquently. Question: You write that you aren’t bothered by the fact that for so many years, Halachic descisions were made by men, since women weren’t educated enough to make those decisions. What about nowadays, when many women are educated? Does it bother you that the dynamics remain the same, where only (male) Rabbanim are allowed to make Halachic rulings?

Thanks for the comment! I think the answer to your question partly depends how one defines “make halachic rulings” – and who decides “allowed” – because depending how we understand those terms, I might question the assumption underlying your question. After all, women have been making halachic determinations of various sorts for centuries, and in general, I think anyone who knows the answer to a question will answer it (or not even think of it as a question in the first place). I wrote that the discussions, etc. – those I read in the written halachic texts – were carried out primarily by men, but I think that’s different from practical rulings on day-to-day issues. Certainly today, women who are more formally educated often make decisions, and many accept their ability to answer halachic questions without issue – either casually (“hey, Friend Who Has Learned, do you know if I have to kasher this pot?”) or formally (such as the Nishmat Yoatzot – who I believe say officially that they don’t “pasken,” but who will certainly answer questions they feel qualified to answer). There is also an increasing number of texts being written by women that analyze the existing scholarship on various issues, some of which even go as far as to offer specific rulings based on those analyses. I think more are coming, and I hope they’ll be judged on their own merits rather than by the gender of the author. Some might think there are technical obstacles to the notion of women offering formal “rulings,” but I’m not sure who defines those lines or where they define them. And some people are also just not used to the idea that women could have learned enough to answer halachic questions; for those people, it’s not a matter of “allowed,” but of getting used to new facts on the ground. I’m sorry that I’m running – I didn’t want to leave your question unanswered, and hope I responded fully and coherently! Please be in touch again if you want to discuss more. You can also check out this article that I wrote several years ago, which addresses some of these issues: https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/save-that-seat/

I once read somewhere, (long ago)that Jewish women did not need to study the Torah or Talmud because they already knew everything ….

l often wonder, that deep down , men have known this subconsciously since the beginning of time, and have sought every reason possible to suppress women.

I have observed over my seventy something years, that women are superior to men in every way except that they are physically smaller and weaker than men.

Could this be the only reason that men are dominant today and historically and Biblically???

Kind regards, Philip

I respect your right to see things differently and i certainly do. we have a whole system of laws made in my opinion by men and sole interpreted by men.

everyday men thank God they are not women. Wow what a great identity to be a woman, when men thank god every day they are not us.

I can’t and won’t even think about participating in a communty where my gender has no voice in the laws.

do men care? some of them do and yahoo, but it never just for one group of people to make laws for another with no input or control on the part of those people.

There are whole tractates where women are a problem for men to figure out how to deal with.

i cannot tell you how many times i was told pulkes pulkes pulkes like it was my job to stop the men from assaulting me and i covered up and they went right on attacking me and other women.

temptresses. the rabbi who only cared that his 3 year old daughters hymen was broken when her cousin attemtpted to rape her. the man who told me i needed to be examined to determine if my hyman was broken when i was raped.

this is madness and i cannot abide it.

husbands breaking wifes vows, fathers doing the same to daughters, the women in the bible who are told that if they dont scream out when they are raped they will be killed for having sex.

it is madness in my view to even spend time on this stuff.

sure keep shabbes, give tsedakah, keep the holidays, but this stuff about women is gross and needs to stop right now

Thanks for your comment, Shifra, and I’m so sorry for what you have gone through – all you have gone through. These rape stories are horrific as are the sick priorities of the people involved. The obsession with blaming women for not being modest enough, when men have their own responsibility to guard their eyes (separate from whatever a woman does) is too much. It is understandable that this whole topic is traumatic and triggering. When Judaism is practiced by dysfunctional people, the result will be abusive. When it is practiced by healthy and thoughtful people, it can be a beautiful way of life. The secular world has a major problem hyper-sexualizing women. Modesty that is chosen and moderate can be a beautiful counterbalance to the objectifying secular take. We have covered all the issues you mention on this site, but I gather that you probably don’t want to read them right now. You want to express your hurt and be validated. So I am so sorry for what you have gone through. It is against the Torah on so many levels. I hope you find comfort and healing.