How and Why Did the Yiddish Language Come To Be?

Dear Jew in the City,

How and why did the Yiddish language come to be?

Best,

Liza

Dear Liza,

Thanks for your question. A few months ago, we discussed Ladino (“Judeo-Spanish”), so I guess it’s only fair that we discuss its Ashkenazic counterpart.

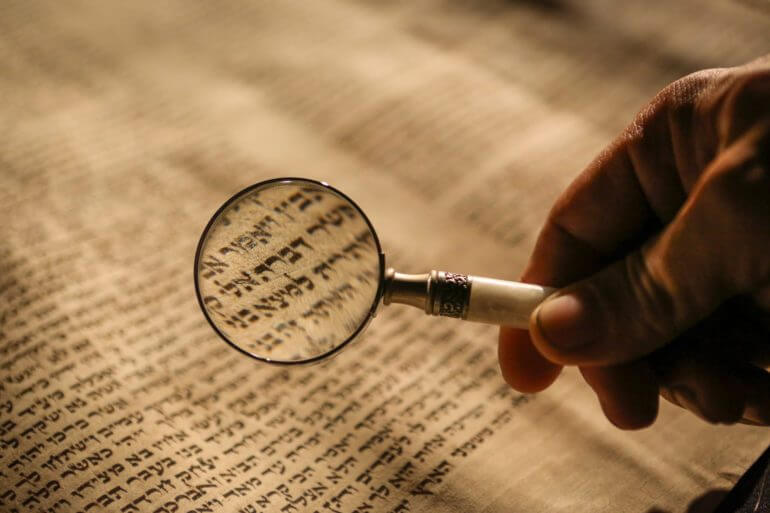

The Yiddish language is over a thousand years old. Literally meaning “Jewish,” it is the language of Jews who were exiled to Central and Eastern Europe from Israel, after the destruction of the Second Temple. It’s commonly thought of as a Jewish dialect of German, or a mash-up of Hebrew and German, but the truth is far more complicated. The grammar of Yiddish comes from West German, but the language also includes influences from Hebrew, Aramaic and a number of Slavic and Romance languages. The exact origins of Yiddish are subject to much debate, so we’ll start with the most accepted theory and then share some alternative ideas.

Most authorities believe that Yiddish began in the 10th century, when Jews from France and Italy migrated to the Rhine Valley in Germany, resulting in a language that combined aspects of all these roots. Further eastward migration spread Yiddish throughout Central and Eastern Europe, including the addition of elements from Slavic languages. Ultimately, Hebrew (the language of the Bible) was reserved for prayer and Aramaic (the language of the Talmud) was used for study, but Yiddish was the language of daily life.

Yiddish was opposed by the leaders of the 18th century Enlightenment, who considered it zhargon (jargon), but it got a boost by the Hasidic movement. By the 19th century, there were millions of Yiddish speakers. In the late 19th century, a modern Yiddish literature movement was spearheaded by such writers as Mendele Mocher Sforim and Sholem Aleichem (both pen names). In 1908, the Czernowitz Conference, an international conference on the Yiddish language, declared Yiddish a national language of the Jewish people.

The Holocaust, however, decimated the Yiddish language. Before World War II, there were 13 million speakers of Yiddish worldwide. The Holocaust killed most of them. In America, Yiddish suffered as immigrants feared its use represented a failure to succeed in their new land. Additionally, many people shunned Yiddish, considering it a form of German, the language of their murderers.

In the early 20th century, evidence was found that Yiddish was not a derivative of German. Rather, Yiddish and German were both descendants of Germanic, much the same way that Italian and Spanish are both descended from Latin. This changed some perceptions. Since the latter half of the 20th century, Yiddish has been studied academically and Yiddish literature has been taken more seriously. In 1978, Yiddish writer Isaac Bashevis Singer (creator of Yentl, among other classic characters) won the Nobel Prize for Literature.

So that’s the most commonly accepted history of Yiddish, but let’s revisit its origins according to alternative hypotheses.

As noted, most scholars believe that Yiddish started in Western Europe and spread eastward, but many scholars now believe that it actually started farther east. One linguist has argued that Yiddish began as a Slavic language but it was “relexified,” i.e., most of its vocabulary was replaced with German words.

Linguist Max Weinreich argued that Yiddish was a Romance language that got Germanized. This would mean that Yiddish was started by Jews who came to Europe as traders with the Roman army, settling in Rhineland. The combination of Hebrew, Aramaic, Romance and German formed a new language rather than a dialect of German. (In the 1980s, Drs. Robert King and Alice Faber found no significant similarities between the Yiddish spoken in Eastern Europe and the German dialects of the Rhineland.)

Another theory that relies on relexification maintains that Yiddish came from Irano-Turko-Slavic origins. Jews participated in the Silk Road trade routes from the ninth to eleventh century. Jewish traders, as a neutral guild with no political agenda, enjoyed special privileges from both the Holy Roman Empire and the Tang dynasty. Accordingly, they had contact with a wide array of languages. Yiddish contains aspects of many languages, all of which were spoken on the Silk Roads.

There are other theories, but the bottom line remains the same. Yiddish is not a bastardized form of German. It’s a language in its own right and, for literally a millennium, it has served as the mameloshen (mother tongue) for millions of Jews.

Sincerely,

Rabbi Jack Abramowitz

JITC Educational Correspondent

Follow Ask Rabbi Jack on YouTube

If you found this content meaningful and want to help further our mission through our Keter, Makom, and Tikun branches, please consider becoming a Change Maker today.

2 comments

Sort by

Why no print function?

Not part of the social buttons we installed. We can try to add it.