Historic Sabbath SCOTUS Ruling Builds On Founding Freedom Of Religion

Last week, in a unanimous decision, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of Sabbath accommodations in the workplace, ruling that accommodation is required unless it causes a substantial burden to the employer’s business. But how did a country founded on religious freedoms take almost 250 years to adequately protect Sabbath observance in professional spaces?

Religious liberty is the foundation stone of American democracy. The Puritans came to these shores in order to be able to practice freely, and the free exercise of religion is guaranteed in the first clause of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

However, for too long the practical impact of the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause was often minimal, at least insofar as people of non-Protestant faiths sought to have their religious practices protected and accommodated in the workplace. For one, although “exercise” by its plain terms implies actions, the Free Exercise Clause was largely viewed as protecting freedom of conscience and private worship, and not freedom of religious practice in the public sphere. In addition, the First Amendment originally applied only to limit the federal government (“Congress shall make no law . . .”), not to states and local governments.

The Supreme Court’s first encounter with a Free Exercise Clause claim came in 1878, in a case called Reynolds v. United States, when a Mormon polygamist challenged his conviction under a federal anti-polygamy law. The Supreme Court rejected the claim that he could not be convicted of polygamy because it was religiously compelled by his faith. Central to the decision was that the Court read the Free Exercise Clause as protecting religious beliefs, not religious practices that run counter to generally applicable criminal laws. Whether this was the right decision or not in this particular case (and there are certainly arguments for why the First Amendment does not protect polygamy), this belief-oriented framework for evaluating Free Exercise Clause claims took hold, making it extremely difficult to win claims based on infringement of religious practices, whether Sabbath observance or otherwise.

The Supreme Court later (in 1934) found the Free Exercise Clause to apply against the states and local governments via the Fourteenth Amendment, which established that no “State” shall “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” And some early 20th Century cases found that the First Amendment protected certain religious practices, in particular the right to educate one’s children in accordance with one’s faith.

Nevertheless, the decisional law largely adopted the distinction between religious beliefs—the freedom of conscience, which is protected absolutely—and religious practices, which were often not protected at all. Critics of the Court’s jurisprudence of this era have noted that the Court was largely adopting a Protestant Christian view of religious freedom, and of religion itself, insofar as belief is sacrosanct, but particular religious practices and restrictions are not (think “circumcision of the heart” rather than actual circumcision). In the workplace, this meant that employers were generally not required to accommodate an employee’s religious practices.

Jews Losing Jobs Every Friday

It was during this time that countless Jews who had immigrated to the U.S. on the promise of religious freedom faced the repeated trauma of losing their jobs every Friday, as they informed their employers that they observed the Sabbath and couldn’t be at work the next day and were told not to come back at all. On Monday of each week, they had to find a new job.

Here are a few of those stories, as told to Jew in the City by their relatives:

Shlomo (Samuel) Walker came to America in 1920 from Czestochowa, Poland where he had once been the official tailor for the German Army. Walker had a family of 12 that he had to support. He got jobs as a custom tailor, doing made-to-order clothing and alterations in New York City and later in the Bronx. According to family history, Walker kept getting fired from jobs for refusing to work on Shabbos (the Jewish Sabbath), and was forced to find a new position each Monday. At one particular job, some costumers came in on Saturday repeatedly asking for him. So the company made a deal with Walker. They asked him if he had a sewing machine at home, which he did (he made all of his family’s fancy suits and apparel). The company gave him work to take home and said if he can make it up on Saturday night and Sunday he can come back on Monday. And the rest is history.

Shlomo (Samuel) Walker came to America in 1920 from Czestochowa, Poland where he had once been the official tailor for the German Army. Walker had a family of 12 that he had to support. He got jobs as a custom tailor, doing made-to-order clothing and alterations in New York City and later in the Bronx. According to family history, Walker kept getting fired from jobs for refusing to work on Shabbos (the Jewish Sabbath), and was forced to find a new position each Monday. At one particular job, some costumers came in on Saturday repeatedly asking for him. So the company made a deal with Walker. They asked him if he had a sewing machine at home, which he did (he made all of his family’s fancy suits and apparel). The company gave him work to take home and said if he can make it up on Saturday night and Sunday he can come back on Monday. And the rest is history.

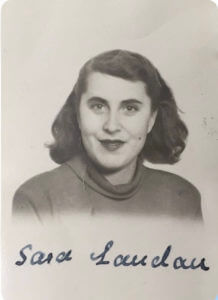

Sarah (Landau) Hamer was born in Hamburg, Germany. Her parents were Polish Jews who were thrown out of Germany in 1938 with their 3 kids. They ended up in Poland and then were sent to Siberia because as Germans, they were Polish enemies. Miraculously, they all survived the war. They were able to leave Siberia in 1946, and went back to Germany to discover their grandparents and most of the extended family killed. From Badneuheim, Germany, they applied for visas to Israel and the U.S. They heard from the U.S. first and moved to Boro Park, Brooklyn in 1949. Hamer worked in an office (after “graduating” from factory work when she finally knew enough English). She loved her job and was only there a few weeks before she got a message to see the big boss. He told her she was doing good work, but why isn’t she coming in on Saturdays? She told him why and he replied that that was then, this is a new country, new times; those traditions are so primitive, but she kept politely saying this is what I do. He told her that unless she would come in on Saturdays too, she no longer had a job. So she thanked him and left his office, unemployed.

Sarah (Landau) Hamer was born in Hamburg, Germany. Her parents were Polish Jews who were thrown out of Germany in 1938 with their 3 kids. They ended up in Poland and then were sent to Siberia because as Germans, they were Polish enemies. Miraculously, they all survived the war. They were able to leave Siberia in 1946, and went back to Germany to discover their grandparents and most of the extended family killed. From Badneuheim, Germany, they applied for visas to Israel and the U.S. They heard from the U.S. first and moved to Boro Park, Brooklyn in 1949. Hamer worked in an office (after “graduating” from factory work when she finally knew enough English). She loved her job and was only there a few weeks before she got a message to see the big boss. He told her she was doing good work, but why isn’t she coming in on Saturdays? She told him why and he replied that that was then, this is a new country, new times; those traditions are so primitive, but she kept politely saying this is what I do. He told her that unless she would come in on Saturdays too, she no longer had a job. So she thanked him and left his office, unemployed.

Civil Rights Act of 1964

The law changed for the better for a brief time with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Although principally motived by and enacted to root out racial discrimination and segregation, in eleven titles it prohibited discrimination based on race, color, national origin, sex, and religion in a wide variety of contexts, including in public facilities (Title III), federally funded programs (Title VI), and employment (Title VII). In particular, as it relates to employment, in addition to forbidding discrimination on the basis of religion, Title VII requires that covered employers provide a “reasonable accommodation” for religious practices, unless providing the accommodation will cause “undue hardship” for the employer.

This was good. But in 1977, the Supreme Court effectively gutted the reasonable accommodation requirement, in a case called Trans World Airlines, Inc. v. Hardison. In that decision, it rejected a claim brought by a Sabbath-observant TWA employee who was fired after he refused to work on Saturday. And as understood by numerous courts over the ensuing decades, the Supreme Court interpreted “undue hardship” under Title VII to mean that as long as the requested accommodation imposes anything “more than a de minimis cost” on the employer’s business, the employer is not required to provide the accommodation. And because arranging for shift-switching was more than a minimal cost, TWA was not required to accommodate the employee’s Sabbath observance.

This reading of Title VII is hard to defend based on the statute’s plain text, as Title VII imposes an “undue burden” standard, which necessarily means something more than “de minimus,” i.e. minimal. But lower courts nevertheless read (or misread) an important sentence in the Hardison opinion to free employers from liability so long as the burden of accommodation was more than trifling. The Hardison decision has had detrimental effects on the protection of religious observance in the workplace for almost 50 years, as employers can almost always find some minimal cost from accommodation.

Article VII Finally Restored

Last week, in a unanimous decision (Groff v. DeJoy), the Supreme Court finally restored Article VII’s reasonable accommodation requirement to its original meaning. In a case brought by a Sabbath-observant postal worker, it held that Title VII requires an employer to show that granting a requested accommodation would result in substantial additional costs to the business.

The Court noted that Title VII’s use of the phrase “undue burden” means that the burden on the employer must rise to an “excessive” or “unjustifiable” level. The Court thus held that the ordinary meaning of “undue hardship” cannot support the narrower, “de minimis” reading of Title VII, and that to the extent lower court’s understood the Hardison decision in that way, they misread it.

The Court also clarified several other issues in religious practice-protective ways. It explained that Title VII requires an assessment of a possible accommodation’s effects on “the conduct of the employer’s business,” not simply on co-workers. Further, “a hardship that is attributable to employee animosity to a particular religion, to religion in general, or to the very notion of accommodating religious practice cannot be considered ‘undue.’” In other words, co-worker or manager bias or hostility to a religious practice or accommodation is not a valid defense or justification for denying an accommodation.

These are all important, welcome, and long-overdue correctives. While we’ll have to see how this latest decision plays out in practice, hopefully it will usher in a new era of respect for and accommodation of the religious practices and needs of individuals of every faith and in every industry–from law to finance to entertainment to sports. In an age of increased awareness of the importance of diversity and inclusion, we can all be thankful for that.

If you found this content meaningful and want to help further our mission through our Keter, Makom, and Tikun branches, please consider becoming a Change Maker today.