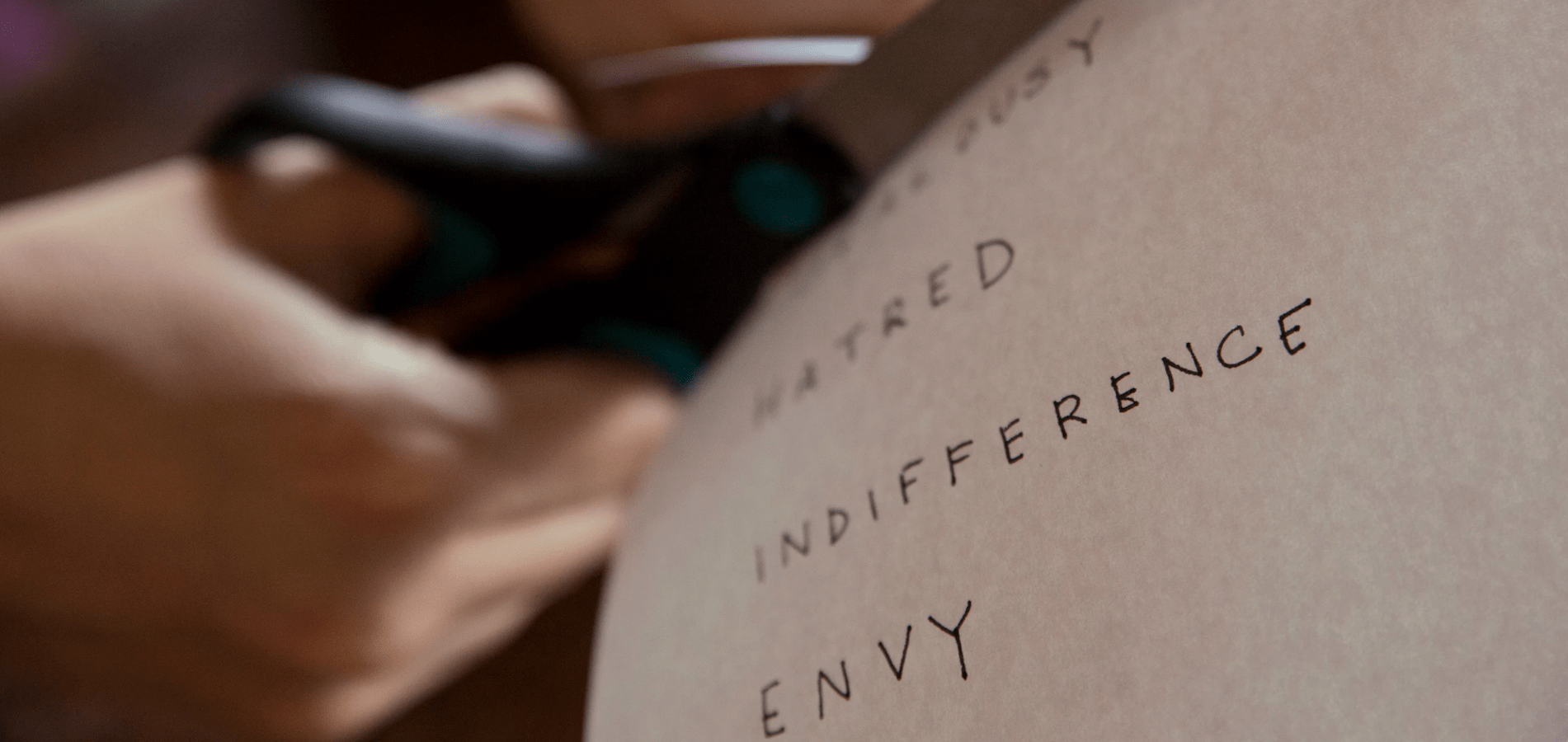

How Can The Torah Command Us Not To Be Jealous?

Dear JITC-

How can the Torah command me to not be jealous of our neighbor? How am I supposed to control my feelings?

Thanks,

R.Z.

Dear R.Z.-

Thanks for your question. I assume that you’re referring to Exodus 20:14, the last of the “Ten Commandments,” which is the prohibition against coveting, though, really, you could also be referring to Leviticus 19:18, the obligation to love others as we do ourselves. (I’ll explain why that is.) But in truth, a number of commandments are about what we think and feel rather than what we do.

Let’s start with Exodus 20:2, which is the first of the “Ten Commandments.” (The reason I keep putting “Ten Commandments” in quotes is because those verses actually contain 14 commandments. In Hebrew, they’re referred to as the Aseres HaDibros – “the ten statements” – which is more accurate than “the Ten Commandments.”)

Okay, Exodus 20:2 is “I am the Lord your God, Who brought you out of the land of Egypt….” Did you ever wonder “What kind of a ‘commandment’ is ‘I am the Lord your God?’” This is understood as an obligation to know that there’s a God.

You’ll note that the obligation isn’t to believe in God, it’s to know there’s a God. The difference is that when you believe something, you’re open to the possibility that your assumptions may be wrong; when you know something, you reject contradictions. You may believe Columbus was a Jew escaping the Inquisition; I don’t believe that but I must acknowledge that the proof either way is inconclusive. But if you were to tell me that Columbus was Ethiopian or that he sailed to China – I will reject those statements as outright falsehoods because I just don’t believe them to be wrong, I know them to be wrong.

So how do we fulfill the obligation to know there’s a God? We do this by looking for Him – in nature, in history, in the Torah, and everywhere else – until we have satisfied our intellects as to the existence of a Creator Who manages His world.

Then there’s Deuteronomy 6:5, “You shall love Hashem your God….” How can the Torah command us what to feel?

Before we answer that, let me ask you a different question: do you hate Hitler? Assuming you answered yes, why do you hate Hitler? I’ll assume that you hate him because you are familiar with his deeds. Well, this works for love as well. The mitzvah to love God requires that we familiarize ourselves with Him. If we get to know God through His deeds, loving Him will be the natural consequence.

Let us now move on to the obligation to love our neighbor as ourselves (Leviticus 19:18, mentioned above). Really, this is the mitzvah that prohibits jealousy because it obligates us to be as happy for our friends’ good fortune as we are for our own. Imagine if your child wins an award. You’re not jealous, you’re proud! Similarly, we should not be jealous of our peers. If we truly love one another as we do ourselves, then it makes no difference whether I win the lottery or you win the lottery, we should both be equally happy whether the good fortune is our own or the other guy’s.

Honestly, this may be easier said than done but I believe that, as with the mitzvos regarding God, the intention here is that we act towards others the way the mitzvah suggests until we actually internalize that feeling of love towards one another. I support this interpretation through the explanation of another mitzvah.

Deuteronomy 10:19 is the obligation to love converts. This may seem strange because converts are already included in the general obligation to love one another. The Sefer HaChinuch explains that this mitzvah means that we must go the extra mile to avoid causing distress to a convert, loving them even more intensely than we do one another. It is apparent from context that our increased love is the result of our extra efforts.

You may recall that, when God gave the Torah, the Jews responded, “We will do and we will hear” (Exodus 24:7). We understand this to mean that we will perform the mitzvos even before we fully comprehend them because only through doing them can we truly come to that knowledge. Similarly, when a mitzvah requires a certain thought, belief or emotion, we perform the actions that will ultimately bring us to that state. The mitzvah isn’t to be in that state spontaneously, it’s to work at getting to that state.

Which brings us to Exodus 20:14, the prohibition against coveting. “Coveting” doesn’t mean being jealous. It means taking steps to deprive another person of that which is rightfully his in order to acquire it for yourself. One does not violate this prohibition until he actually takes some action towards getting the object away from its owner. (This includes acquiring the object legally by putting the owner under duress.) An example of this mitzvah being violated is the way in which the evil queen Jezebel acquired the vineyard of Naboth for her husband, King Ahab, in I Kings 21.

In his commentary, the ibn Ezra explains this mitzvah as follows: certain things are simply ridiculous for a person to desire. My go-to example is that, whatever life brings, I’m never going to marry Queen Rania of Jordan. There is simply no path that leads to that outcome. Just like a person puts such ideas out of his head, he should also recognize that what God has given another person is equally out of bounds and he should just forget about it. One must learn to be happy with his lot in life and to see others’ possessions as taboo. The idea of attempting to acquire that which God has given another should seem ludicrous to us.

So, really, this mitzvah is also an attitude-adjustment but not for jealousy (which is actually addressed by the mitzvah to love one another). By refraining from activities associated with coveting, we ultimately come to a greater appreciation for what God has given us.

Learn more about the ideas underlying these and other mitzvos in Rabbi Jack’s book The Taryag Companion, available on amazon.com.

Sincerely,

Rabbi Jack Abramowitz

JITC Educational Correspondent

If you found this content meaningful and want to help further our mission through our Keter, Makom, and Tikun branches, please consider becoming a Change Maker today.