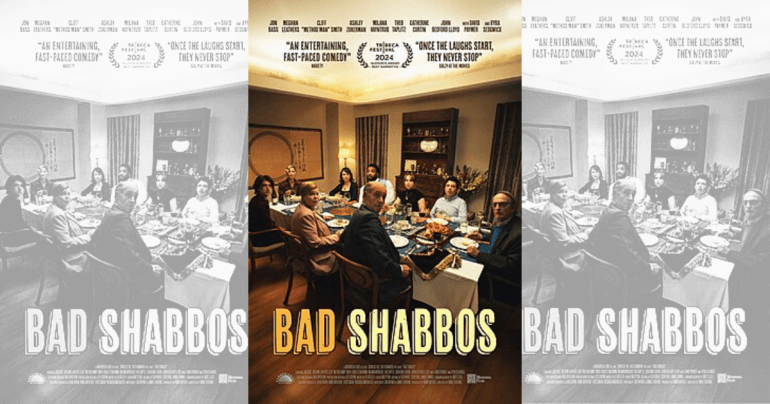

Bad Shabbos Movie Review

Bad Shabbos: The Good and the Bad

by Allison Josephs

I had been hearing about the indie film, Bad Shabbos, over the last year but didn’t get around to watching it until it recently came to Netflix. While people said they loved it and that it was hilarious, several of our readers reached out saying how disturbing they found it to be. JITC Hollywood Bureau’s director, Cindy Kaplan, and I are usually aligned on most issues. On this film our opinions somewhat diverged. As we debated what we loved and hated, I suggested that we each write a review. While we have general guidelines of what we’re looking for in Jewish representation, at the end of the day, we’re dealing with art and it will hit people differently. And with no further ado, here’s my take. Scroll down for Cindy’s more positive one!

Let’s start with the good. The casting is authentic. It’s all Jews playing Jews, and they are attractive by and large. The family is observant but not Hasidic. Maybe they are modern Orthodox or Conservadox. This is a slice of Jewish life rarely seen on the big screen, and that’s noteworthy, since most Jews on screen are super secular or super religious. The family is not ostentatiously rich and the men are not nebbish. The Jewish women are not JAPs. The Shabbos candle lighting scene is pretty nice, David’s non-Jewish fiancé, Meg, shares some meaningful words of Torah during the Shabbos dinner, and she seems sincere about her conversion to Judaism. There’s also some positive Israel representation. The younger brother, Adam, wants to join the IDF, wears their t-shirt, and the whole family speaks positively about it. There’s sort of Black Jewish representation. While the scene consists of a Black man pretending to be Jewish, it gives voice to the fact that this community exists, and that’s a nice teaching moment. Perhaps the most significant positive element of Bad Shabbos is that the plot of the movie does not revolve around being Jewish. Far, far too often, shows and films about Jews make Judaism the problem. In Bad Shabbos, covering up an accidental death is the problem. Although, as you will see later on in my review, that angle is also one of the most troubling parts of the film for me.

What I liked less. I’ll break my complaints into inaccuracies, silly Jewish tropes, Orthodox Jewish tropes, and dangerous Jewish tropes.

Inaccuracies: When the guests (the adult children) arrive on Friday afternoon, everyone says “good Shabbos” to each other. The correct greeting would be “good erev Shabbos” – “good afternoon before Shabbos.” I understand that in Reform and Conservative circles people say “Shabbat Shalom” to each other as a way of saying hello all day on Friday, so “good Shabbos” would be the Orthodox equivalent of that. I’ve just never seen that done.

For the candle lighting, the correct way to do it is that only the person lighting waves her hands and makes a blessing. In the film, only the mother lights the candles, but the daughter (Abby) and girlfriend (Meg) do the waving and blessing too. The candle lighting is also done when it’s quite light outside, even though it’s supposed to be as the sun is setting. What is supposed to happen after that in a modern Orthodox home is that some or all of the people go to services. You’re also not supposed to eat or drink until you hear the kiddish blessing over wine or grape juice, which is done after services.

All of this is wrong in the film. The women light candles and everyone sits around drinking alcohol and no one goes to shul or mentions that they should be going to shul. There’s a major plot point that happens during the drinking, but it could have been done pre-candle lighting. It could have been the reason people missed shul. The supposedly modern Orthodox family does not know the Hebrew alphabet. They struggle to sing a song about it. It was very odd. And finally, although this is a Sabbath observant family, as the father, Richard, is trying to figure out how to get rid of the dead body, he’s sitting in his bedroom with the light on and a pen and papers on his bed on Friday night. This is all wrong. Bedroom lights are off and pens are away and not used on Shabbos.

Silly Stereotypes: The film begins with two old Jewish men telling a joke in a stereotypical Yiddish accent. Can you still find Jews who talk like this? Of course. Does it set the tone of the movie that we’re going to see something stereotypical? Yes. When we first meet our two main characters, David and Meg and we see that the Jewish guy is bringing the blond non-Jewish woman home to his parents I nearly groaned out loud. We have seen this tired trope again and again. It’s really time for something new. Likewise, the mother is a bit of an overbearing type, when she complains about how Meg is cutting the watermelon. She’s also judgmental over her daughter’s relationship. The overbearing Jewish mother is overdone. So is the sickly Jew, and we get three instances of that. Adam, the younger son, is the mentally ill and heavily medicated Jew; his father, Richard, is the neurotic Jew, constantly turning to self-help books to ease his anxiety; and the boyfriend, Ben, is the GI issues Jew, who has colitis.

Religious Jewish Tropes: Tropes for religious Jews usually consist of pushiness around religious practice, hypocrisy in practice, and making fun of the “silliness” and “stupidity” of the Talmud or Jewish law. This film delivers in those ways, but thankfully does not give us subjugated Orthodox woman or going fully unorthodox. Pushiness comes out when Abby literally yanks Meg over to light the Shabbos candles. In a normal situation, the prospective convert or less religious Jew would be extended an invitation to participate, but would not be dragged. Then, despite being from a shomer Shabbos family, both Abby and David acknowledge that they don’t always keep Shabbos. In fact at the end, David makes a promise to God that he’ll keep Shabbos for the rest of his life if they make out of the situation okay, but then breaks the promise a moment later.

The most upsetting part of the film’s religious Jewish representation for me was the mocking of Jewish law. I remember in my pre-observant days how ridiculous we thought Orthodox Jews were with all their nonsensical rules, caring more about irrelevant minutia than actual values. There are certainly some Jewish laws that are difficult to understand, and when they are referenced quickly, without the proper framework, they sound outright kooky. We get this experience in the film, when a family of religious Jews is trying to figure out how to dispose of a dead body. Instead of being overcome by the gravity of a man dying on their watch, the father, Richard, is concerned with how to move the body on Shabbos (which is prohibited) and offers that placing a challah or baby on the body will magically fix everything. This is a perfect segue to my final set of criticism.

Dangerous Stereotypes: I understand that the point of the film was to be “Weekend At Bernies” with all the laughs and hijinks, but a more Jewish version. This doesn’t work for me because when we see religious Jews on screen, we automatically have expectations that they will have a certain moral high ground, and if they don’t, they are desecrating God’s name, the Torah, and all they stand for. Additionally, scheming Jews is a really bad look. Although the characters in the film did not murder the dead guy, they spend the whole movie figuring out how to cover up his death. This plays into the most evil and dangerous tropes about plotting Jews. And one more dangerous trope is Adam, the boyfriend, being the philandering Jew. He wants David to have a wild bachelor party, checks out Meg’s backside, and cheats on his girlfriend.

Final thoughts: Because Jews are accused of so many bad things, often opposing things – being both too pious and too sexually deviant, being both nebbish and pushy, being both weak and sickly, and powerful and scheming – it is REALLY, REALLY difficult to tell a story without touching on any of those themes. That being said, most TV shows that are written and produced in Israel seem to avoid almost all the typical tropes, so I know it’s possible. I believe the intentions were good here, but writers and showrunners need to be aware of what to potentially avoid. This movie made some important progress but there’s more work to do.

Bad Shabbos is Good Jewish Representation

by Cindy Kaplan

When I first heard about Bad Shabbos, an indie dark comedy from Menemsha Films, I was cautiously excited. Cautious, because I’ve analyzed enough Jewish representation on screen to know that it often misses the mark. Excited, because it’s exactly the kind of movie I’m drawn to, and it co-starred Cliff “Method Man” Smith, who, as I’ve argued to whoever will listen, is one of the most underrated actors working right now. His performance in Starz’s Power Book II: Ghost would have earned him an Emmy if the show had cracked through to the white-dominated zeitgeist; I mention that here because the Power Universe is a prime example of minority representation that’s edgy, subverts as many tropes as it leans into, and straddles the line between being accessible to outsiders and built for insiders, and I think Bad Shabbos does much the same thing.

The plot is fairly simple: a family is set to host their eldest son’s non-Jewish soon-to-be in-laws for Shabbat dinner when there’s an accidental death, and they need to cover it up so their youngest doesn’t go to prison. As a film, Bad Shabbos lives up to its genre, balancing high stakes, wacky hijinks, and a tight plot. And it works as a film precisely because it leans into its Jewishness. Similarly, it works as an artifact of Jewish representation precisely because it prioritizes the tropes of the genre over the tropes of the people.

One of the recommendations we make at JITC Hollywood Bureau is to have more Jewish stories where the characters’ Jewishness is not the source of conflict. In this way, Bad Shabbos is a huge success. While the characters all observe Shabbos somewhat differently and relate to their Judaism differently, they are all unapologetically Jewish and do not blame Shabbos or their identities for the unfortunate situation they find themselves in. The conflict is that there’s a dead body in the house and they can’t let it be discovered by the outsider in-laws, the cops, or anyone else. That it’s set at Shabbos dinner is fun, culturally specific, and increases the stakes and humor, but it’s not at all central to the conflict. These are Jews simply being Jewish when the kind of situation that could happen to anyone happens to them.

At the same time, the characters’ Jewishness is not an afterthought, but a core part of their personalities and their family lives. The youngest son is proudly obsessed with the IDF and a particular brand of Israeli machismo. The oldest son commits to God that if they get through the ordeal, he’ll keep Shabbos in the future. His fiancé shares a moving dvar Torah she learned through her conversion courses. Most strikingly, the dad, who is a true person of the book, quoting self-help book after self-help book to guide his life, turns to the Gemara to find a solution. He quotes Shabbat 43B, where Rav Hanina bar Shelemiya says in the name of Rav, that in order to move a corpse on Shabbat, one may place an infant or loaf of bread on it.

This might seem absurd, and I can see the argument that this could make non-Jewish audiences think Jews are crazy. Why are we worried about the halacha of moving a corpse on Shabbat when we’re covering up a possible accidental murder? Why would bread or a baby solve this problem? But there’s a stronger argument to be made that representation is not only about how others see us, but seeing ourselves on screen. If you love Gemara like I do, its integration into a farcical dark comedy is nothing short of wonderful. The Talmud is filled with the rabbis debating far-fetched scenarios, and their ability to create absurd thought exercises to get to the heart of the Torah and halacha is one of the core ways Judaism has sustained itself through the millennia. The loaf of bread gag asks, “What if the Gemara’s hypothetical actually happened?” Seeing the daf come to life in a movie on Netflix is fun and validating. The antisemites take enough from us; let us have pride and joy in the richness of our texts.

There are two other scenes that highlight the film’s success in creating inside jokes for us Jews. To distract the non-Jewish future in-laws, the father and son come up with a fake ritual, the “men’s chant.” They begin a niggun, and when asked by the mother-in-law why women can’t participate, the son improvises an answer that Eve ate from the Tree of Life so women can’t participate. There are so many layers to the joke: poking fun at how “weird” non-Jews think Jewish rituals are that a fake one can seem real; the realistic touch of an impromptu, improvised niggun, and again, the reference to Jewish texts (e.g. there’s an opinion that women don’t drink from Havdalah wine because of Eve’s sin). Another “in” joke is when Method Man’s character, Jordan, who absolutely loves Jews, traffics in antisemitic tropes that he doesn’t realize are antisemitic. Many Jews have had an experience where the non-Jews in their lives don’t realize the centuries of antisemitic conspiracy theories have seeped into their understanding of us, and it’s hardest when we know the person repeating these hateful comments is lacking self-awareness more than they are filled with hate. It’s a meta experience that’s difficult to talk about, but there it was on screen.

The film took some artistic license that took me out of the story – the misplaced Shabbat candles, the incongruousness of a child from a clearly learned Conservadox family not having a basic understanding of the aleph-bet (and singing it to the tune of the ABCs.) I also wish the mother was a more imaginative, less trope-y character (even though she did have a great arc). These deviations served to situate the film within the larger context of how people understand Jews on screen; with more positive, nuanced, subverted, and authentic representation, perhaps audiences won’t need these cheats. That says more about the state of Jewish representation across the board than it does this particular film.

Ultimately, Bad Shabbos was a Jewish movie that embraced its Jewishness and placed Jews in the center of a story we aren’t usually invited to be in. Unlike so many projects where the creative feedback is, “Why do the characters have to be Jewish?” Bad Shabbos retorts, “Why can’t they be?”

If you found this content meaningful and want to help further our mission through our Keter, Makom, and Tikun branches, please consider becoming a Change Maker today.

1 comment

Sort by

Honestly, the plot sounds so horrific that I’m not sure how this could possibly look good for Jews to be involved in. I always wonder if there was more true talent in the writers, would they be able to write a fabulous piece that has no horror or immorality in it.