What Is The Meaning Of The Shema Prayer?

Dear Jew in the City,

I saw that the Shema was trending recently. Can you tell me a little bit about this prayer?

Sincerely,

Jonah

Thanks for your question, Jonah. There’s a lot to say about Shema. For starters, did you know that it’s a mitzvah? I don’t mean that it’s a mitzvah to recite Shema (which is also true), I mean that Shema itself is a commandment. The Torah says, “Listen, Israel: Hashem is our God; Hashem is One” (Deuteronomy 6:4). This is a commandment to know that God is unique and that He alone runs the world. By saying, “Listen, Israel…” the Torah takes this statement from being a mere observation about the Oneness of God to an obligation for us to be aware of it.

Let’s take the Shema word by word:

- Shema doesn’t just mean to hear something. When the Torah says that God heard someone’s prayers, it means that He accepted them and acted upon them. Similarly, shema means that we should accept the statement about God’s unity and proceed accordingly;

- Yisroel means Israel, the Jewish people. It’s grammatically singular but conceptually plural. The obligation of Shema applies to each of us individually, but all of us together are like molecules in a single body;

- Adonai is a substitution for the ineffable (i.e., unpronounceable) Name of God, which is spelled YHVH in Hebrew. YHVH is a portmanteau of hayah (was), hoveh (is) and yihiyeh (will be). This Name of God alludes to God’s eternal existence: He is, He always was, and He always will be;

- Eloheinu – our God. The Name Elohim refers to God’s might (as well as to powerful individuals in certain contexts). When we say Eloheinu, we refer specifically to the fact that God has performed mighty deeds for us and for our ancestors (thereby enabling us to be here today!);

- Adonai – there’s that eternal existence of God again;

- Echad – God is One. This doesn’t just mean that there’s only one God, though that is certainly the case. It means that God’s unity is absolute. He can’t be subdivided, neither physically nor conceptually. We speak of God having a number of attributes, but that’s just to facilitate our human understanding. In truth, God’s will, His wisdom, His might, His compassion, and anything else you might attribute to Him are all One, indivisible in a way we can’t truly comprehend.

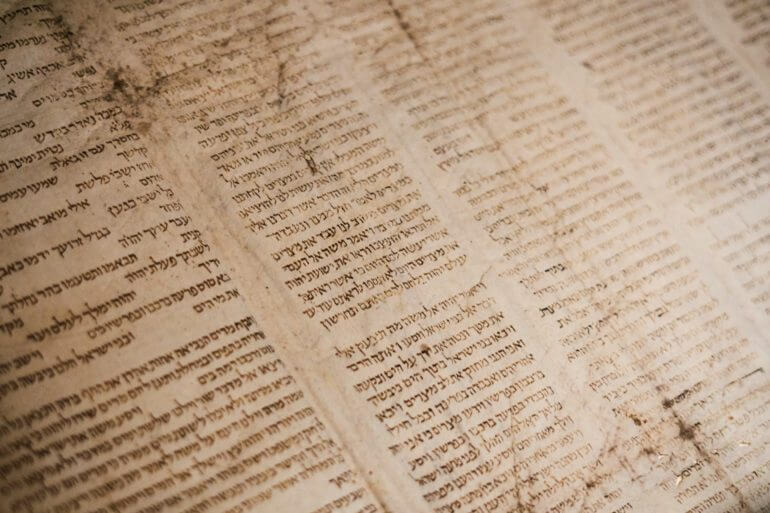

In the Torah – and in many siddurim – you’ll find two letters of the Shema written larger than the rest: the ayin of the word Shema and the dalet of the word echad. Most people will tell you that this is because these two letters spell the word eid – witness – and that by reciting Shema we are testifying to Hashem’s unity. This may be so, but I prefer another, perhaps more pragmatic, explanation.

There are two “silent” letters in Hebrew: alef and ayin. Shin-mem-ayin means “listen,” but shin-mem-alef means “perhaps.” The ayin is written oversized to draw our attention to it, so we don’t err and say, “Perhaps, Israel, Hashem is our God….” Similarly, the letters dalet and reish look very similar. Alef-ches-dalet means “one,” while “alef-ches-reish means “another.” The oversized dalet keeps us from misreading and saying “there is another God” (God forbid!), which would be the exact opposite of “Hashem is One!”

The verse of Shema is followed by the silent recitation of a line that doesn’t appear in Scripture: Baruch Shem kavod malchuso l’olam vaed – “Blessed be the Name (of the One), the glory of Whose kingdom is forever and ever.”

There are several explanations for the inclusion of this statement, as well as for the silence of its recitation. According to the Midrash in Devarim Rabbah, when Moshe ascended to the Heavens to receive the Torah, he heard the angels singing this praise to God. Being a good form of praise, he brought it back down to Earth with him. However, he cautioned the Jews only to recite it silently. The Midrash compares this to a person who stole some jewelry from the royal palace and gave it to his wife. He warned her not to wear them in public, lest they be found out. For similar reasons, we recite this praise discreetly, except on Yom Kippur. On that day, we are considered tantamount to angels and therefore worthy of expressing this praise aloud.

Next comes the section of V’ahavta – “You shall love Hashem your God…” – which comprises Deuteronomy 6:5-9. These are the verses that immediately follow Shema in the Torah. Collectively, these verses constitute what is called kabbalas ohl malchus shamayim – accepting the yoke of the kingdom of Heaven. In other words, when we recite the Shema, we acknowledge that God is King of the universe and that we are His subjects. (You may have noticed that Shema is one of the verses of Malchiyos – God’s Kingship – that we recite on Rosh Hashana. This is why.)

Next comes the section of V’hayah im shamoah – “It will be, if you faithfully hearken to My commandments that I command you today…” (Deuteronomy 11:13–21). This is referred to as kabbalas ohl mitzvos – accepting the yoke of the commandments. In other words, we acknowledge God’s mitzvos and that they are incumbent upon us. The Talmud in Brachos (13a) explains that first we accept God as King over us, after which we acknowledge that we are subject to His mitzvos.

The paragraph of V’hayah repeats some ideas that are stated in V’ahavta but in the second-person plural rather than singular. This again stresses the idea that these things apply both to the individual and to the community.

Finally, there’s the section of VaYomer (Numbers 15:37–41). This section focuses heavily on the mitzvah of tzitzis, but it includes so much more. The Gemara (Brachos 12b) tells us that the paragraph of VaYomer includes five themes. In addition to the mitzvah of tzitzis, it includes mentions of accepting the mitzvos, rejecting heretical thoughts and overcoming our passions. These are all important things, but the main reason the paragraph is included in the recitation of Shema is because it includes zeicher yetzias Mitzrayim – a remembrance of the exodus from Egypt. The Torah tells us, “Remember the day when you left Egypt all the days of your life” (Deuteronomy 16:3). We fulfill this obligation through our recitation of the Shema.

All told, the Shema has 245 words. To these we add three words, either Eil Melech ne’eman – “God, faithful King” – when davening alone, or Hashem Elokeichem emes – “Hashem, your God, is true” – recited by the shaliach tzibbur when davening with a minyan. (This is the standard Ashkenazic practice; there are others.) Doing so brings the total to 248 words. But why should we want Shema to be exactly 248 words?

There are a number of things that total 248. There are 248 positive mitzvos (“Thou shalts”) in the Torah. The numerical value of our forefather Avraham’s name is 248. But the one that interests us here is that there are 248 limbs and organs in the human body. (Of course, the number of body parts depends on how you divide things. If you ever played a game of Hangman with someone who draws all the fingers and facial features, you know what I mean. Specifically, there are 248 limbs and organs in the human body for purposes of ritual impurity, based on the Mishna in Oholos 1:8.) The reason we want Shema to equal 248 words is because, according to the Zohar Chadash, each word of Shema spiritually nourishes one of our bodily limbs.

I think we’ve covered quite a bit, but there’s a lot more that could be said about the Shema. There are many fine books that can help you gain a deeper appreciation for this, as well as for other parts of our liturgy.

Sincerely,

Rabbi Jack Abramowitz

JITC Educational Correspondent

Follow Ask Rabbi Jack on YouTube

If you found this content meaningful and want to help further our mission through our Keter, Makom, and Tikun branches, please consider becoming a Change Maker today.