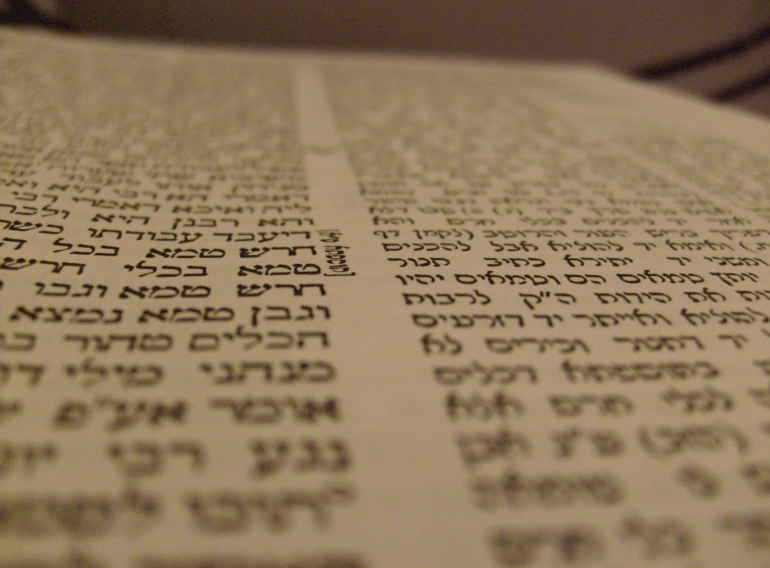

What Are Some Positive Talmudic Teachings Worth Learning?

Dear Jew in the City,

You recently published an article disproving some of the negative things that people claim are in the Talmud. Can you please share some of the positive things that are in it?

Thanks,

Joana

_

Hi Joana,

Thanks for your request. “Positive things” is a broad stroke and it can include a lot of different things. For example, while a lot of people will accuse the Talmud of being sexist, it was actually quite progressive. By way of illustration, the property rights afforded women were unprecedented for its time. Similarly, some people complain about Talmudic jurisprudence, but the more you know about it, the more you recognize that it was way ahead of the curve. Because of the material to which I’m responding, however, I’m going to focus on things in the Talmud (and other books of Chazal) where the Sages discuss our relations vis-à-vis non-Jews. I’ll give three well-known examples.

First, the Talmud in Brachos (17a) tells us that Rabbi Yochanan Ben Zakkai, who was the leader of the Jewish people, always greeted others first, including random non-Jews he would pass in the marketplace. That doesn’t sound terribly racist or hateful!

Next, remember the famous Sifra (a book of Midrash) in which Rabbi Akiva calls loving one’s neighbor as oneself (Leviticus 19:18) the “great principle of the Torah”? Well, as well-known as that dictum is, most people don’t realize that the discussion isn’t over and Rabbi Akiva doesn’t win the debate. Ben Azzai proposes a different verse that he says is greater still: “This is the book of the generations of Adam” (Genesis 5:1).

This is interesting. “Love your neighbor” seems profound, while “This is the book of the generations of Adam” looks pretty mundane. But nothing could be further from the truth! The problem with loving one’s neighbor is that the idea of “neighbor” can be pretty subjective. If someone has a TV, wears the wrong kind of yarmulke, votes for the wrong candidate or acts in any other way with which I disagree, I might decide he’s not my neighbor. I could hate a lot of people and still consider myself in compliance with this obligation.

“This is the book of the generations of Adam,” however, is pretty unambiguous. Every single human being on the face of the planet – black, white, yellow, red, brown; Christian, Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, Jew – every single one of us is descended from the same first parents. I may not agree with everything you do – nor you I – but we’re all one brotherhood of man, so we’d better act like it!

Along similar lines, consider the famous dictum that one who saves a life is as if he saved an entire world (Sanhedrin 37a).

“But wait,” I hear some of you object. “That says ‘one who saves a Jewish life….’”

Well, it does and it doesn’t.

First off, that’s the version of the Mishna cited in the Babylonian Talmud. The version cited in the Jerusalem Talmud just says “one who saves a life…” (Yerushalmi Sanhedrin 4:9). Not only that, there are at least two editions of the Mishna (Parma MS 3173 and MS Kaufmann A 50) in which the text just says “one who saves a life” and not “one who saves a Jewish life.” The version cited by the Rambam in Hilchos Sanhedrin (12:7; in some editions, 12:3) also says “one who saves a life.” All this makes me suspect that “one who saves a life” was the original text and “Jewish” was a later insertion.

The context of this dictum also supports this hypothesis. Let’s take a look. The Mishna in Sanhedrin reads:

Adam (the first person, from whom we are all descended) was created alone to teach us that one who destroys a single life is as if he destroyed an entire world, and one who saves a single life is as if he saved an entire world.

Since it talks about Adam – from whom all mankind is descended – it just makes more sense if it’s talking about humanity as a whole, as in the Yerushalmi.

Continuing its discussion of Adam, the gemara in Sanhedrin (38a) teaches us that Adam was created alone so that no person could claim superior ancestry since we all come from the same place. Teachings such as this reiterate the concept of the brotherhood of man.

Look around and you’ll find many dicta that promote this idea. For example, the gemara in Gittin (61a) teaches that we support needy non-Jews, visit sick non-Jews and bury deceased non-Jews, the same as we do for Jews, in order to promote peaceful relations between us and our neighbors. [For similar reasons, we violate Shabbos to save non-Jewish lives just as we do for Jewish lives – see Iggros Moshe OC 4:79, et al.] Also, in Gittin (62a), we see that we can’t assist our non-Jewish neighbors with their harvests during the Sabbatical year (shemittah); this is because of our own restrictions on agricultural labors at that time. Nevertheless, we should wish them success with their harvests and offer them words of encouragement as a sign of our support.

So, counter to the out-of-context quotes and outright lies accusing us of hateful attitudes towards our non-Jewish brethren, you’ll find plenty of authentic quotes intended to promote peace and brotherhood. Yes, the Talmud was redacted under Roman persecution, and you will find laws and attitudes reflecting the tensions of that reality, but nothing in it is motivated from an ethnocentric hatred of others. Given our druthers, we’d live in peace and harmony with everyone.

This is just one of many areas in which the much-maligned Talmud doesn’t get credit for what’s actually in it.

Sincerely,

Rabbi Jack Abramowitz

Educational Correspondent

Follow Ask Rabbi Jack on YouTube

If you found this content meaningful and want to help further our mission through our Keter, Makom, and Tikun branches, please consider becoming a Change Maker today.

1 comment

Sort by

I think the point about ways of peace could be stated more strongly. To quite Maimonides (Laws of Kings 10:5):

“… Our Sages commanded us to visit the gentiles when ill, to bury their dead in addition to the Jewish dead, and support their poor in addition to the Jewish poor for the sake of peace. Behold, Psalms 145:9 states: ‘God is good to all and His mercies extend over all His works’ and Proverbs 3:17 states: ‘The Torah’s ways are pleasant ways and all its paths are peace.'”

Notice that he associate seeking peace with the most religious of ideals – the feature that characterizes the Torah and most fundamental to G-d’s ways.