Why Can I Choose My Hashkafa But Not What Halachos I Keep?

Dear JITC,

I’m not always clear when something a commentator says is from Sinai and when it’s their own interpretation. What makes one able to say, “I don’t hold by Rashi or the Maharal,” but not able to say “I don’t hold by the Chofetz Chaim’s laws of gossip? And if it’s because one is halacha (law) and one is hashkafa (philosophy), then why am I able to pick and choose the hashkafos that feel right to me, but not able to pick and choose the halachos that were established based on those hashkafos?

Best,

Julia

—

Dear Julia,

Thanks for your question. Let’s first address the idea of picking and choosing halachos. We discussed this once before. There, we cited an incident from Talmud Pesachim 52b. There it tells us of Rav Safra, who brought barrels of sabbatical-year wine from Israel to another land, requiring that they be burned. He was traveling with Rav Huna and Rav Kahana, and he asked how their teacher Rav Avahu ruled on the question of whether such produce must be returned to Israel for burning, or whether it could be burned where they are. Rav Kahana reported that Rav Avahu ruled stringently, while Rav Huna said that he ruled leniently. Rav Safra decided to rely on Rav Huna’s more lenient opinion, since Rav Huna was known to be meticulous about what he learned from his teacher.

Pursuant to the preceding incident, Rav Yoseif disagreed with Rav Safra “shopping” for opinions in this way. In doing so, he cited the verse from Hoshea (4:12), “My nation asks advice of its wood, and its staff gives it to them.” The word “maklo” (its staff) is understood as referring to one who is meikil (lenient), i.e., to people who gladly accept any lenient ruling they hear.

Another objection to picking and choosing is based on Chulin 43b-44a (also found in Eiruvin 6b-7a). There we are told that one may choose between following authorities of equal stature, but one must follow both the leniencies and the stringencies of his choice. If one follows only the leniencies of the different authorities, he is considered evil, and if he follows only the stringencies, he’s considered foolish. It’s fairly obvious why one who always takes the easy way out is considered evil, but the one who always takes the hard path is considered foolish not just for making his life more difficult. He’s considered foolish because always acting stringently leads to inherent contradictions. Rashi on 7a gives an example of this, which I previously shared here.

It is for reasons such as these that Chazal told us, “Get yourself a teacher” (Avos 1:6 and 1:16). As the Bartenura explains, we should have more than one teacher, but only one who’s our halachic “go-to guy.” It’s important to note, however, that you get to choose your teacher. Once you do, however, you’ve chosen to follow his halachic positions.

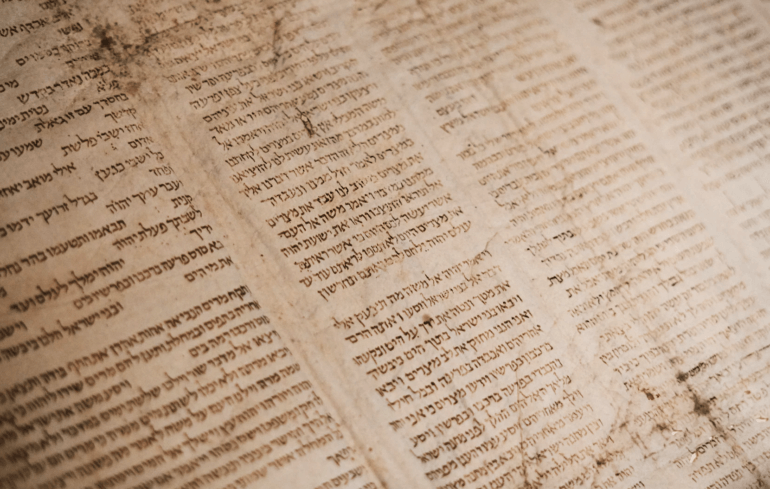

Torah is from Sinai, but that doesn’t mean that it’s not also the authorities’ “own interpretations,” as you put it. There’s no contradiction. The Torah itself tells us that the Torah is no longer in Heaven (Deuteronomy 30:12) – it was given to us to interpret – and we are obligated to follow those interpretations, be they what they may (Deuteronomy 17:11). If I’m of Ashkenazi, Sefardi, Yekkishe or Chasidishe descent, then I’m born into a community that follows Ashkenazi, Sefardi, Yekkishe or Chasidishe authorities. Of course, even without changing communities, there’s still a lot of wiggle room in who to follow. Some people follow Rav Moshe Feinstein, others follow Rav Soloveitchik, and still others follow Rav Hutner. And, of course, there are the yeshivos we choose to go to (which have roshei yeshiva and rebbeim) and the cities in which we choose to live (which have their own rabbis). These rabbis may say different things sometimes, but that’s okay. As the Talmud tells us (Eiruvin 13b), both opinions reflect God’s will! (The preceding statement excludes the occasional actual error stemming from not knowing or misapplying some point of law. It happens. Humans are fallible.)

But opting out of following the Chofetz Chaim’s laws of gossip? Good luck finding a halachic authority who disagrees with those! Not speaking lashon hara is a Torah commandment. The Chofetz Chaim didn’t make those rules up, he just collected them. If you did find a rabbi who rejected those laws, I wouldn’t recommend making him your rebbe!

That’s halacha. “Halacha” means “law” and laws, by nature, are binding. (If they weren’t, they wouldn’t be laws, they’d be suggestions!) But hashkafa is philosophy. You can’t legislate philosophy. Philosophy speaks to us internally. So you can choose your own hashkafa much like you can choose your own rav. But just like there are some “rabbis” of whom I’d be wary (such as any of them who reject the Chofetz Chaim’s laws of lashon hara), there are likewise going to be hashkafos that don’t pass the sniff test.

The Rambam has a rationalist approach. That speaks to me, which is why you’re going to find me citing the Rambam very often and the Maharal not so much. But if you have a more mystical bend, go for that approach. As we said above regarding halacha, both opinions reflect God’s will!

Matters of hashkafa typically have little practical application. It makes little difference whether you believe “olam haba” refers to a future time or where you go after you die, so there’s little need to compel anyone to believe in a particular set of hashkafos. But, as with halacha, there’s still a limited number of hashkafos from which to choose. This is why it’s important to get hashkafos from your rabbis and teachers as well.

I’m not going to name any for you, but I imagine you can think of at least a few things that label themselves as Jewish while espousing ideals that are in fact antithetical to halacha. Many well-meaning people latch onto such things because they lack the proper grounding to differentiate between kosher hashkafos and foreign ideas. So just like you should choose a rav in matters of halacha, you should choose one in matters of hashkafa. (Optimally, I’d think this should be the same person, but if having two different people floats your boat, then so be it.) If you’re a rationalist like me, choose a rationalist; if you have the aforementioned mystical bend, then choose someone with that approach. As in matters of halacha, get yourself a qualified teacher.

As far as your last point, about being able to pick and choose hashkafos but not the halachos that were based on those hashkafos… well, I disagree with your assertion that halachos are based on hashkafos. Rather, I think that halacha and hashkafa evolve together. Hashkafos like Chasidus, Religious Zionism and Torah im Derech Eretz didn’t spring spontaneously into existence like Athena from the skull of Zeus (look it up). They developed based on what preceded them, as a part of our mesorah (chain of tradition). And just like some aspects of Sefardi, Ashkenazi and Yemenite halacha evolved a little differently, the halachos of people subscribing to different hashkafos may have evolved a little differently.

I attended a yeshiva in Israel that didn’t recite Hallel on Yom Ha’atzmaut (Israel Independence Day). A friend of mine changed schools because he wanted to be someplace that recited full Hallel, with a bracha. This wasn’t a quibble over one halachic issue; he needed to be in a place that better aligned with his hashkafos. Halachos and hashkafos go hand in hand. If you’re in a place – geographic or metaphorical – where the halachos don’t align with your hashkafos, then you may need a new spiritual leader in one or both of those areas.

Just remember that hashkafa, like halacha, is part of our mesorah. Sabbateanism wasn’t a kosher hashkafa, nor was Samaritanism, and neither are umpteen other things that exist today. Without proper guidance, one is in at least as much danger of stumbling in matters of hashkafa as in matters of halacha. So, as we’ve said… get yourself a rabbi!

Sincerely,

Rabbi Jack Abramowitz, JITC Educational Correspondent

If you found this content meaningful and want to help further our mission through our Keter, Makom, and Tikun branches, please consider becoming a Change Maker today.